These notes are written in the warmth and comfort of my library, long after the cold and chill of the arctic has been warmed from my feet and hands. But the memories of these wondrous frozen lands are still bright and vivid, indelibly set in my mind. I had a chance to follow in the footsteps of the famous 19th-century arctic explorers, Ross, Perry, Franklin, McClintock, Rae and Simpson; those brave men who undertook to discover the Northwest Passage. Walking the barren lands inspires a private feeling of original accomplishment that is so elusive in today’s society.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Have you known the great white silence?…..

Have you broken trail on snowshoes?….

Dared the unknown, led the way, and clutched the prize?….

Have you marked the map’s void spaces?…

Have you suffered, starved and triumphed, groveled down,

yet grasped at glory,

Grown bigger in the bigness of the whole?

“Done things” just for the doing….

Seeing through the nice veneer the naked soul?

The simple things, the true things, the silent men who do things….

….the Wild is calling….let us go.

These random lines from Robert Service’s Call of the Wild best reflect my innermost feelings about the North. Everyone has his quest—wealth, fame…….mine is to do things, to leave a legacy of life.

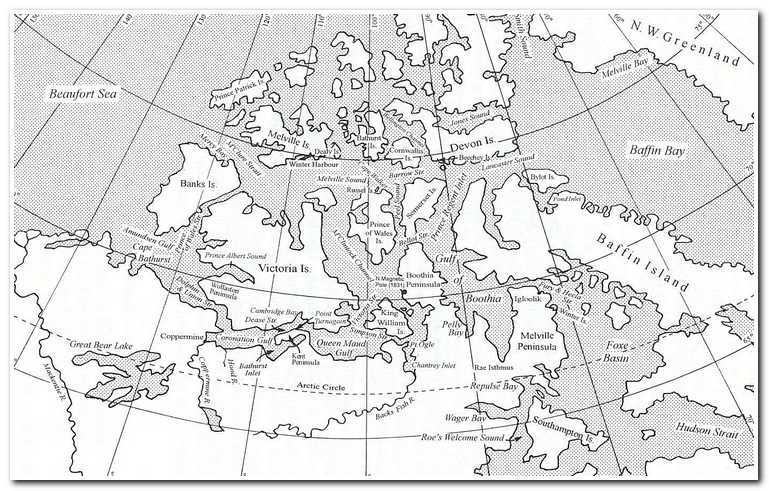

King William Island 1846-1848

In May of 1845 Sir John Franklin was sent by the British Admiralty on an expedition of discovery to find a northerly route through the arctic ice to the Pacific Ocean, the fabled Northwest Passage. The British had been engaged in this effort for several hundred years and at long last thought that success was nearly within their grasp. Most of the North American arctic shoreline had been explored and only a few hundred miles of unknown territory near King William Island remained blank on the maps. The Admiralty put Franklin in command of the expedition and outfitted two ice-ready ships the Erebus and the Terror to make the journey.

From London Franklin’s two ships went up the east coast of England to Stromness in the Orkney Islands were the ships took on more food and water. By early July they reached the Greenland coast and on the 12th they started across Baffin Bay toward Lancaster Sound, the eastern entrance of the Canadian arctic.

The Admiralty had given Franklin instructions to sail west through Lancaster Sound and Barrow Strait as far as Cape Walker. At Cape Walker they were to turn south and then west toward Bering Strait. Once Franklin’s ships had traversed the as yet unknown route from Cape Walker to the North American coastline they would be in known waters again and the exploration of the Northwest Passage would be completed.

During their first season away, the Erebus and Terror were unable to proceed south once they reached Cape Walker and were forced to set up a winter camp at Beechey Island. During that first winter three men died and were buried on a small knoll just above the shoreline.

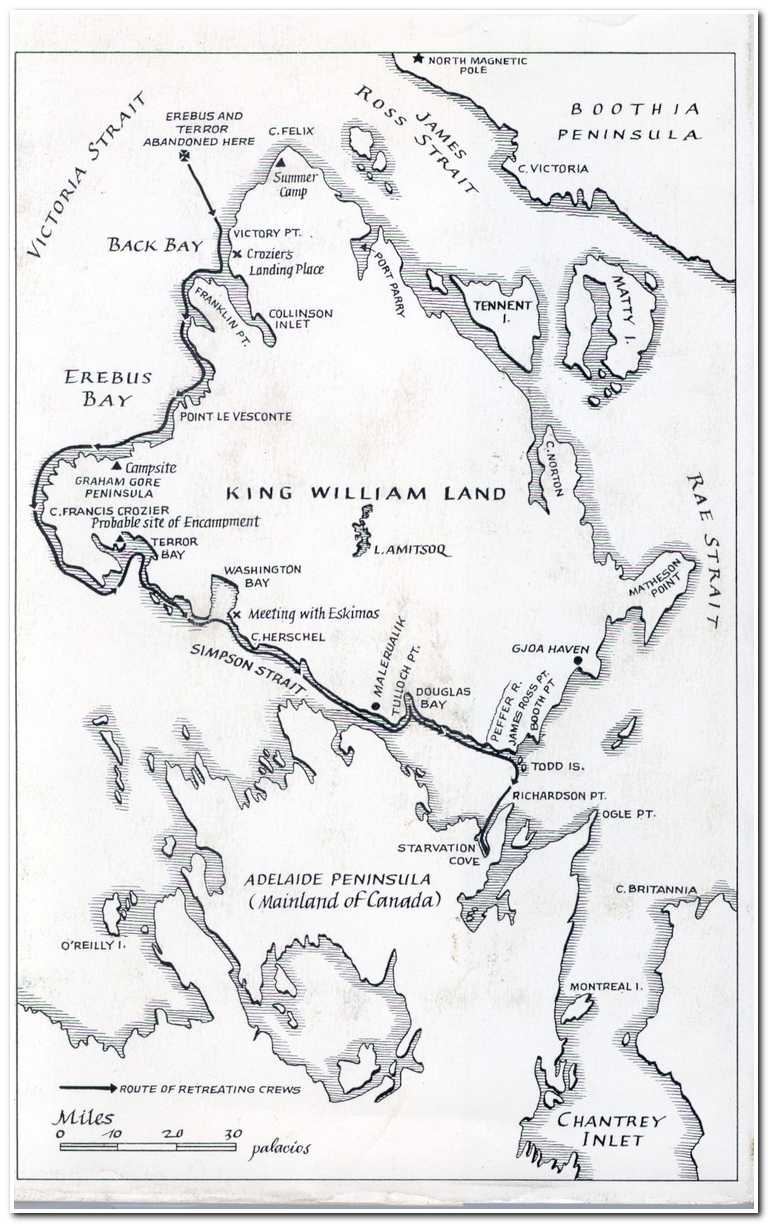

In August 1846, after the ice in Barrow Strait broke up, Franklin set off for Cape Walker. Ice conditions were much better that summer and the Erebus and Terror were able to sail nearly unobstructed, south from Cape Walker and toward the North American coast. However, on September 12th, as the ships neared King William Island heavy ice was sighted and soon closed in around the ships. Franklin and his crews found themselves trapped, unable to force a route farther through the ice. Or to retreat. They were only 77 miles from a cairn built by Thomas Simpson in August 1838. Seventy-seven unexplored miles were all that remained.

With the Erebus and Terror now beset, the crews prepared the ships for winter. They built a canvas enclosure over the decks, piled emergency provisions and supplies on the ice near the ships and removed the sail rigging. They dismantled all but the lower masts. One topmast on which to run up a light as a beacon to shore parties was left. They were now fully prepared to spend another winter in the ice and wait until the following summer.

By May 1847 the midnight sun returned and the weather warmed enough that a shore party was sent south to explore, on foot, the remaining unknown coastline to Simpson’s cairn. Then on June 11th Franklin died and Captain Francis Crozier of the Terror assumed command.

June, July and August passed and still the ice remained unbroken. Soon it became obvious to Crozier that any hope of breaking free that year was quickly fading and that the Erebus and Terror were going to spend a third winter in the arctic. When the ships had left England they had been provisioned for three years, which meant that by the following May the goal of the expedition was no longer going to be getting through the Northwest Passage. The goal now was to survive.

The third winter proved deadly. Scurvy broke out among the crews and twenty-one men died. Crozier realized that the party would have to abandon the ships, head south and try to escape overland, hoping to find enough food along the way. There was relief at Fort Resolution on the Canadian mainland. On April 22, 1848, Crozier judged that everything was in readiness and the one hundred and five surviving officers and men of the Franklin expedition abandoned the ships in which they had set sail from England with such high expectations three years before.

During the next several months the men of the Erebus and Terror struggled under harness, pulling sleds carrying their small lifeboats and their remaining provisions. One by one they fell victims to exhaustion, scurvy, hypothermia and finally starvation. A few struggled on as far as the mouth of Back’s Great Fish River. But there the last to die fell.

It was the compelling saga of the lost Franklin expedition that inspired me and my companions to undertake an expedition to the shores of King William Island in late March of 1977 to try and recapture a sense of what it must have been like for those men one hundred and thirty years before us. Even before our first footsteps on the arctic ice we felt the call of the wild.

KING WILLIAM ISLAND 1977

There are strange things done in the midnight sun

By the men who moil for gold;

The Arctic trails have their secret tales

That would make your blood run cold;

The Northern Lights have seen queer sights,

But the queerest they ever did see

Was that night on the marge of Lake Lebarge

I cremated Sam McGee.

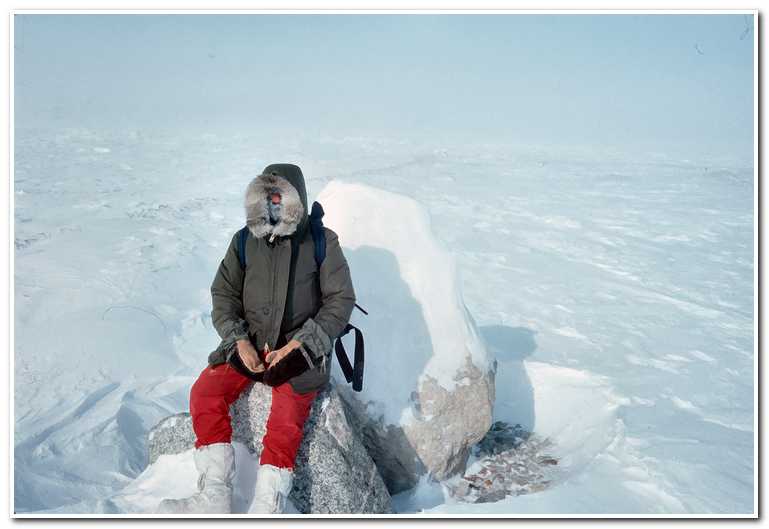

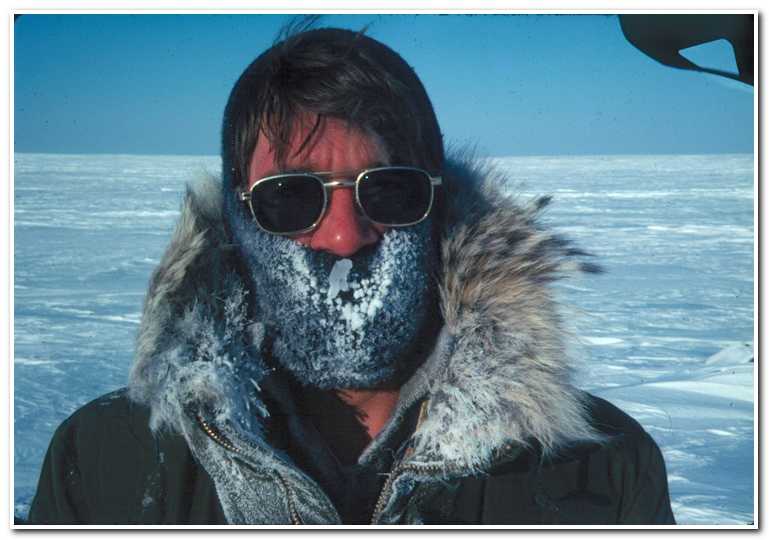

March 24, 1977. Flying to the arctic in March is a shock to one’s middle-class sensibilities. Leaving the temperate 40F of the Pacific Northwest for the frigid –32F in the Canadian arctic was a journey that transcended the thermostatic controls of everyday American life. It was bitter cold as we stepped off the plane in Cambridge Bay on Victoria Island. The arctic air, at that temperature, has feeling and shape. It stung and bit; fingers burned, and nasal passages numbed. But the excitement my two fellow arctic adventurers, Al Errington, Bill Dougall, and I felt was inescapable. The snow and ice on the ground crunched and squeaked dryly as we walked across the tarmac to the tiny prefabricated building that served as the air terminal. There we met Ken Murphy, one of the local bush pilots, who flew a De Havilland Twin Otter aircraft in and out of small Inuit settlements scattered around the Canadian Arctic. We loaded our 400 pounds of equipment and food into Ken’s red van and started for his small pre-fabricated house on the outskirts of town. My thoughts were of the days ahead, the unknown and the fear and excitement that came with it.

Everything was cold, the truck, the doorknobs, everything I touched. I began to wonder if it ever got warm here. To take our minds off the intense cold we started asking idle questions like, “Cold isn’t it?” and “How many people live here?” Ken, in the self assured style of all arctic residents, answered with affected disinterest. It became clear that in his mind he would be patient but aloof with us “southerners.” We spent the next few hours eating, drinking coffee (a favorite arctic pastime) and swapping tales of “derring do”, all embellished and designed to impress the listener and enhance history. After convincing him that we were not total novices, Ken voiced an interest in our plans “Why would anyone want to hike the coast of King William Island?” We told him of the historical fascination of this place; he told us of his hope to leave the arctic and move south after he made his fortune. By midnight we were ready to sack out on Ken’s living room floor; we spent a sleepless night rethinking the genius of spending the next ten days man-hauling a sled along one of the most desolate coastlines imaginable. Yet, in our minds we were “hard men” and had come to a hard country to test our mettle against King William Island’s southern coastline, retracing the last days of the lost Franklin expedition.

Now Sam McGee was from Tennessee, where the cotton

blooms and blows.

Why he left his home to roam ‘ round the

Pole, God only knows.

He was always cold, but the land of gold seemed to

hold him like a spell;

Though he’d often say in his homely way that

“he’d sooner live in Hell.”

March 25 – 7:15 a.m., –32.3F, wind 10 – 15 mph, wind chill –45F. We got up, repacked our sleeping bags and made a breakfast of bacon and eggs – the last real meal we were to have for a week. It was a sunny and cloudless day, but a light ice fog clung to the ground and extended to an altitude of about 100 feet. This cut horizontal visibility to about 3 miles. Ice fog is an interesting phenomenon unique to extremely cold climates whereby minute, blowing ice crystals from the surface of the snow remain suspended in the air creating a fog-like effect. If you look directly overhead, you see a perfectly clear blue sky overhead between 30 and 100 feet up, but when you look straight ahead through the ice crystals you get the impression of ‘fog’. The horizontal visibility can be limited to 100 feet or less.

10:00 a.m. We left Cambridge Bay and flew an hour and a half over the frozen Queen Maud Gulf separating Victoria Island from King William Island. Below, the gulf appeared to be a huge white blanket stretching as far as the eye could see. The feeling of immenseness was overpowering. The smooth white surface of the sea ice was occasionally broken by pressure ridges forced up under the huge pressures on the ice flow generated by winds, currents and tides. These pressure ridges ran for miles and disappeared in the distance.

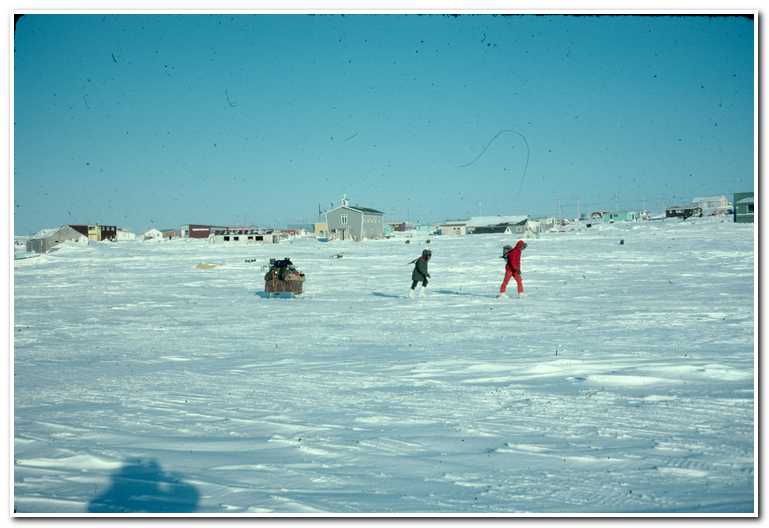

Flying with us were Eskimo (Inuit) people returning to Gjoa Haven, a small settlement on King William Island, after a trip ‘outside’ to Cambridge Bay to visit friends and relatives. The Inuit children, with their cherubic round faces, beautiful black hair and large coal black eyes, unabashedly stared at the funny white men who had come to walk across the ice. To them we were Kabloona (white men with big stomachs).

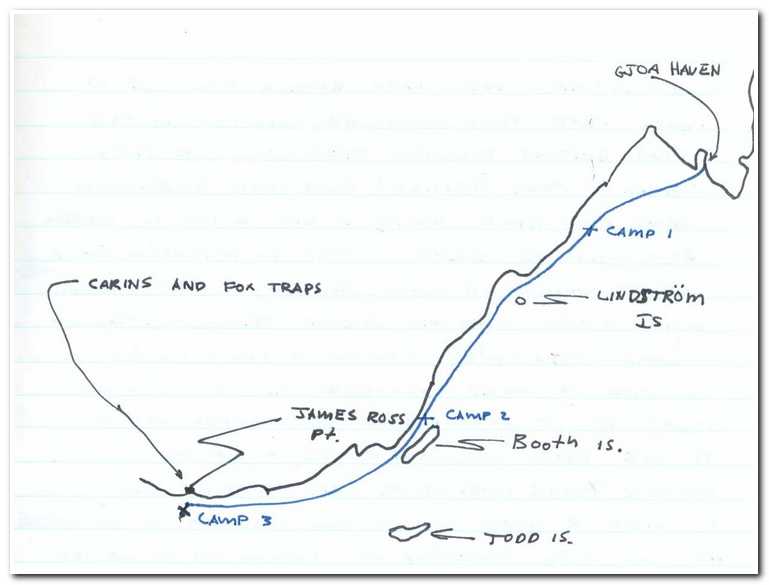

11:30 a.m. We landed at Gjoa Haven 68 ½ degrees north. Gjoa Haven is named for Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen’s little ship GJOA. Amundsen and his crew sailed the GJOA through the Northwest Passage in 1903-07 and spent their first winter in this little bay on the south side of King William Island. Amundsen described it as the “finest little harbor in the world…a veritable haven of rest for us weary travelers”. For hundreds of years it had served as a camp site for Inuit hunting caribou or fishing the rivers along the south shore of the island. Now it is in effect a jail for a dying culture. The white man has created a prefabricated village, with a school and hospital, even a grocery store. However, by concentrating this many people in a relatively small area, the Inuit have lost their birthright of living off the land. Most Inuit now live on welfare; wards of the state that “civilized” them. Gjoa Haven was the starting point for our planned one hundred plus mile trip westward toward Washington Bay.

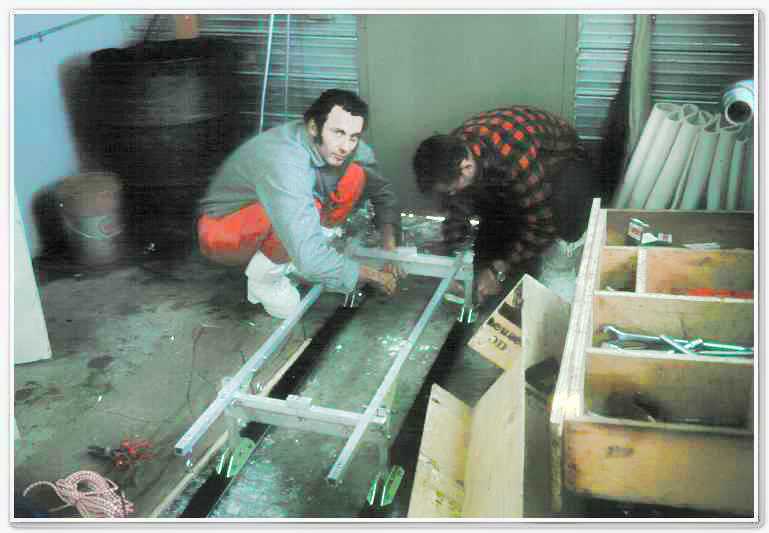

As interesting as the village was, we knew we must continue on our way. The intense, ever-present cold nurtures procrastination in even the most gung-ho among us. Howard showed us to a small maintenance warehouse where we assembled our sled and packed our gear. This process was witnessed by the locals with great curiosity as they pondered the strange white men who were going hiking in the winter; no self-respecting Inuit would. As we were packing, one Inuit asked us if we had a Coleman lantern for our tent.

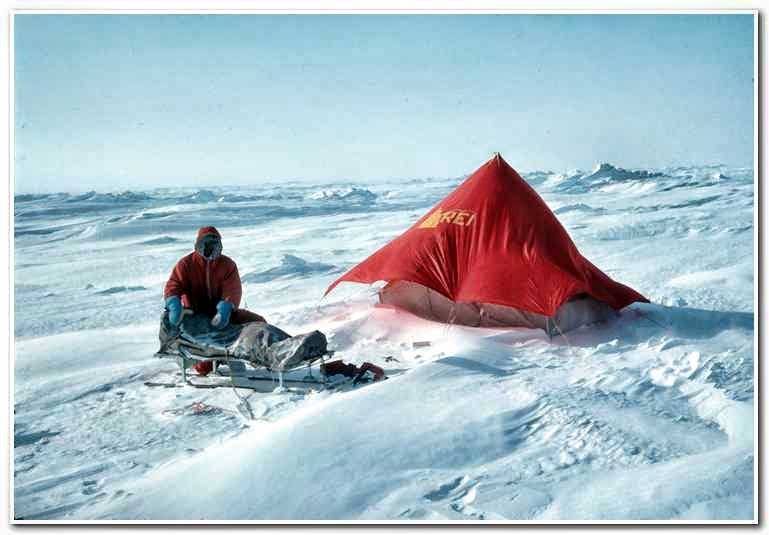

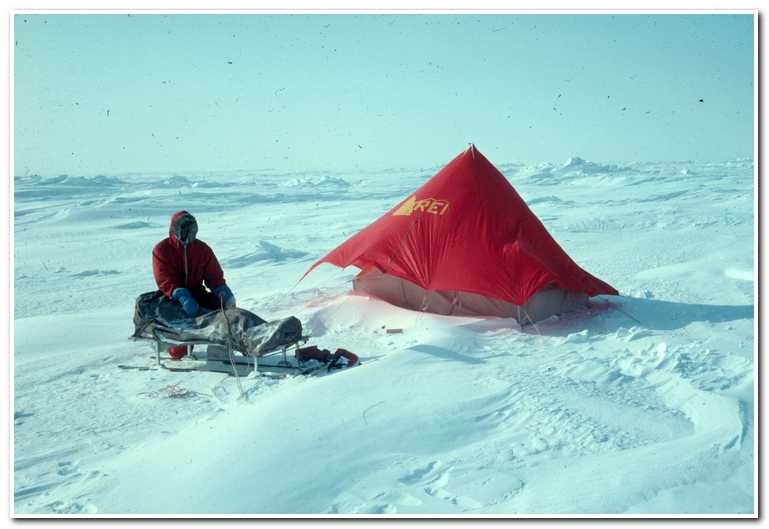

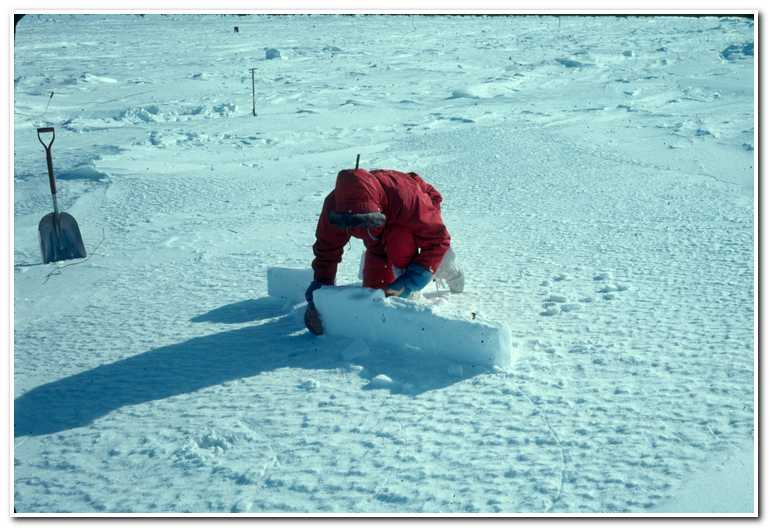

4:00 p.m. The sled was assembled and packed; we were as ready as we were going to be. Since we could put it off no longer, we harnessed ourselves to the sled and set off across the ice on our first arctic adventure. We pulled the 400lb sled for two hours and learned that it was perhaps the most fiendishly difficult labor anyone had ever devised. Any thoughts that this “arctic outing” was going to be fun soon evaporated. Leg and thigh muscles burned; shoulder muscles cramped – we literally inched our way forward. Although the sea ice was flat it was covered with shallow drifted snow that the wind packed into rock hard one foot high ridges which multiplied our work. The ridges often caused our untested top-heavy sled to capsize. When this happened it took all three of us to right it again before resuming our all-out straining in the harnesses. We soon discovered that we could make better time if only two “mules” pulled and one walked beside the sled to steady it. Our initial effort lasted two hours before we stopped and set up camp. The thermometer read –30F.

Though we had two stoves only one worked, a potentially serious problem. The ability to melt water was vital. Even though we were walking over an ocean of water, and snow was everywhere, at this time of year all water was in solid form. We also had trouble with our lantern but finally got it going. The problem turned out to be that the leather seals in the pressure pumps of the white gas fuel tanks froze in the extreme cold and had to be thawed in order to work. The solution to this problem was for one of us to sleep with the seals in our sleeping bag to keep them from freezing. The arctic had already created some strange bed-fellows! The first night we found the lantern was capable of heating the tent to a balmy +5F while the temperature outside dipped to –30F. Even though we were all very experienced mountaineers, this new environment was so intense that, it took us three hours set up the camp and cook dinner that first night.

9:30 p.m. With some reluctance, we put out the lantern, our only heat source, and began our first night on the trail.

On a Christmas Day we were mushing our way over

the Dawson trail.

Talk of your cold! through the parka’s fold it stabbed

like a driven nail.

If our eyes we’d close, then the lashes froze till some-

times we couldn’t see;

It wasn’t much fun, but the only one to whimper was

Sam McGee.

March 26. 7.00 a.m. We got up after a fitful night’s sleep. Actually “got up” is a very shorthand way of putting it. The temperature inside the tent was –25F so, needless to say, we didn’t leap from our sleeping bags, get dressed and put breakfast on to cook. Instead, a strict ritual was developed. On waking I would sit up and, while still in my sleeping bag, reach out, reinstall the pump leathers, and quickly pump up the pressure in our white gas stove and lantern fuel tanks; carefully light both; then lay back down for fifteen minutes while heat built up in the tent and raised the inside temperature above 0F. With the tent initially warmed I would sit up again and put a pot full of snow and ice on the stove and quickly lie back down again and wait fifteen minutes while the ice and snow melted and the water came to a boil. By this time the inside temperature of the tent was 15F at floor level but a comfortable 30F at chest height. I was then ready to emerge from my sleeping bag, quickly dress, and begin cooking breakfast. Only then did Al and Bill acknowledge the new day. Al wore contact lenses, so the cold dry arctic air made “putting in his eyes” a challenge. Bill was lucky; he suffered only from being the oldest member of the expedition and claimed an “age deferral” from being the first to rise. Breakfast usually consisted of two cups of coffee or hot chocolate, freeze-dried scrambled eggs, freeze-dried peaches or pears, and perhaps a piece of fudge for dessert.

After breakfast, we packed up camp. This task too, became ritualized with each of us responsible for different tasks. I was responsible for the cooking gear, lantern, and my personal gear, Bill was responsible for striking the tent and his personal gear and Al was responsible for stowing our gear on the sled and lashing everything in place. After some practice, we were able to get up, cook, and eat breakfast and fully load the sled in one in a half to two hours. The first morning it took 3 ½ hours!

10.30a.m. We started off on our first full day in the harnesses. The temperature was –12F, the wind 20 –25 mph, and wind chill –52F. The day already promised to be a challenge to our endurance and tenacity.

While in harness I was totally drawn within myself; focused only on pulling, on making another 20 steps then fifty or maybe even one hundred steps. The wind always seemed to be coming head-on and would burn my cheeks and numb my chin. Step by step we went on, straining in the harness and soon feeling a kinship to Franklin’s men on their death march around this same coastline 130 years before us. The work took a total commitment to both the mind and the body.

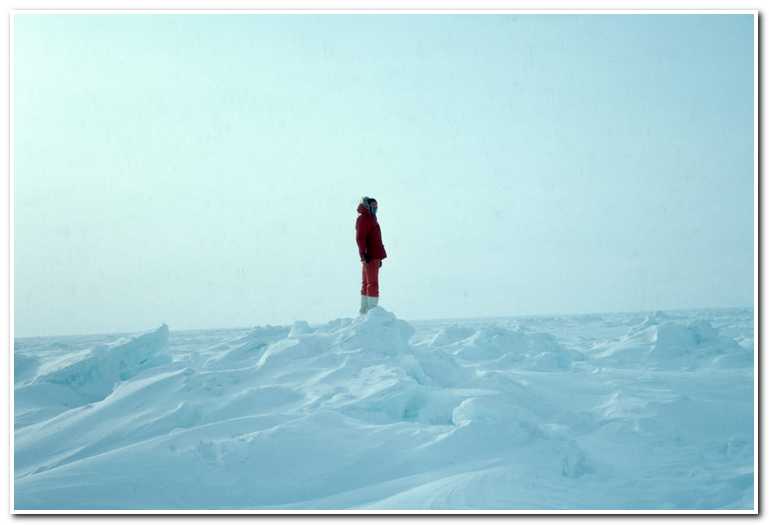

It was utterly silent except for the sound of snow blowing across the ice like sand across the desert. The snow on the surface of the sea ice was constantly shifting, forming intricate patterns on the ice that ran to the horizon and beyond in all directions. It is difficult to point to a time in my life when I felt so inconsequential in my surroundings. That morning we pulled for two hours and made 3 ½ miles before breaking for lunch.

12:30 p.m. We stopped for lunch. This meant unpacking and setting up the tent to provide shelter from the wind while we boiled water and made a hot meal to replace the calories lost to the cold and hard work. Lunch consisted of two cups of soup, each with a big slice of butter melted into it to provide much need fat calories, a full freeze-dried dinner, and two cups of coffee or tea.

In the bitter cold food is fuel. It is used by the body both for working and warming. Once the body uses up its available fuel it immediately tires and gets uncontrollably cold. It only takes perhaps 15 to 20 minutes to go from a state of being comfortable to being morbidly cold. As soon as we started to feel, “low on fuel” we stopped and ate something to refuel the engine. To put our energy expenditure in prospective we allotted 5000 calories per day each, in planning our meals. We used every one of them. In spite of this intake, we each lost ten to fifteen pounds during the expedition.

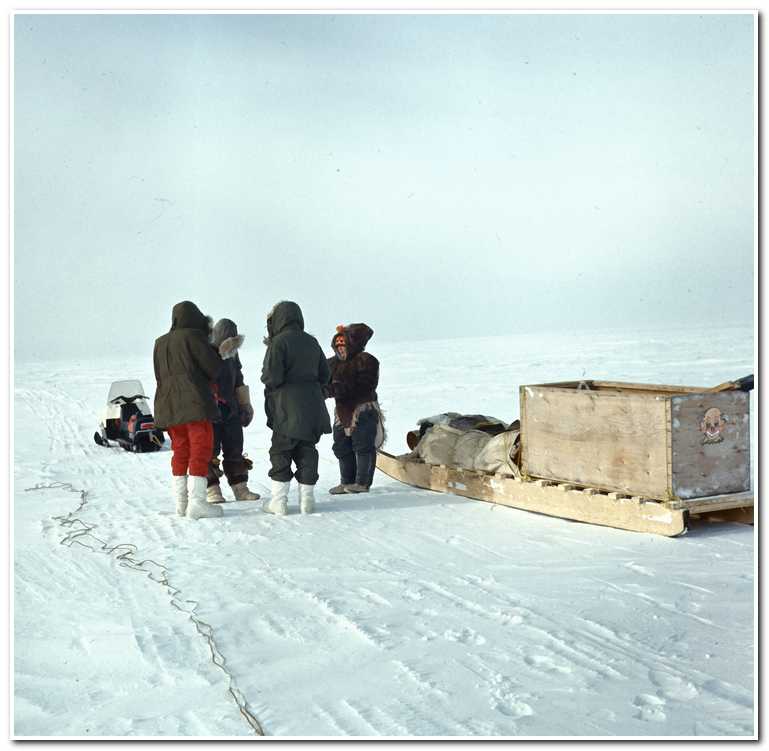

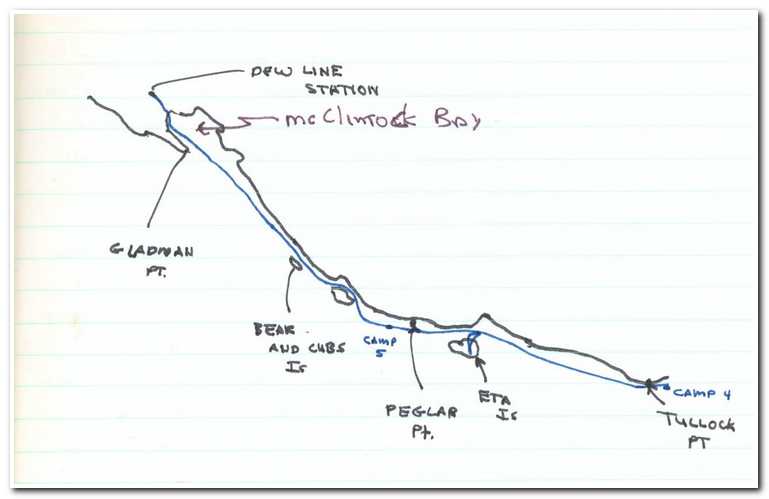

While having lunch we met a man and his wife riding their ski-doo and pulling a komatik (sled) from Gjoa Haven to visit friends at the Gladman Point DEW (Distance Early Warning) Line station sixty miles down the coast. After lunch the ice smoothed out for a while and so we tried three men on the sled again and made better time, 3 hrs and 6 miles — 2 mph!

Pulling a heavily laden sled is still the worst labor ever devised by man. We leaned into the traces, shoulder and chest muscles aching, constantly trying to find the ever-illusive easy way to do it. One step at a time, each one hard fought and despised. We mumbled oaths at the slightest need to change the routine or pace; all the while convinced our teammates weren’t pulling their share of the load.

6:05 p.m. The team pulled on through the afternoon and made camp near Booth Island, 13 miles from Gjoa Haven. The temperature had risen to –12F with the wind at 20 mph. While making camp I was filling the stoves and lantern with white gas and managed to spill some on my right hand. The combination of the cold wind and evaporation of the gas froze the skin and immediately raised several large painful frozen blisters on my hand. In spite of this I made dinner and we treated ourselves to a dessert of fruitcake soaked in bourbon, heated by setting it on a tin plate fastened to the top of the Coleman lantern. We were able to get the inside tent temperature up to +10F. Suddenly life was good again.

As we were getting ready for bed it came clear that our sleeping bags were beginning to ice up. In the arctic, a bigger, heavier sleeping bag is not necessarily warmer. While sleeping the body naturally sweats, giving off water vapor which then migrates from the inside of the sleeping bag, next to the skin at 98.6F, toward the outside of the sleeping bag at –30F. The problem is that the water vapor freezes at the 32F line within the down layer of the sleeping bag. After several nights the bag literally has an icy down layer which then melts each night when the “warm” camper crawls into the bag. This makes for damp nights and loss of insulation over time until the bag can be dried and the process started again. The solution to the problem is to use a double bag system. A smaller inner bag is mated with a larger outer bag. The inner bag moves around inside the outer bag as the camper moves in his sleep and “pumps” the warm moist air out between the two bags before it can freeze inside either bag.

After dinner we talked, commiserated and “chain” read (reader #1 read 20 pages, then tore them off and passed them along to reader #2 who read them and passed them on the reader #3 until the entire book was read by all three readers) “SHOGUN”.

10:00 p.m. Lights out. We slept well after a hard day’s work.

And that very night, as we lay packed tight in our robes

beneath the snow,

And the dogs were fed, and the stars o’erhead were

dancing heel and toe,

He turned to me and “Cap,” says he, “I’ll cash in

this trip, I guess;

And if I do, I’m asking that you won’t refuse my last

request.”

Well, he seemed so low that I couldn’t say no; then he

says with a sort of moan:

“It’s the cursed cold, and it’s got right hold till I’m

chilled clean through to the bone.

Yet ‘taint being head-it’s my awful dread of the icy

grave that pains;

my last remains.”

March 27; 6:45 a.m. After a damp night, we got up at 6:45 am, cooked breakfast, and were on the trail by 10:15 am. It was still windy, 15 mph. The temperature was -14F, the wind Chill –51F, and ice fog made visibility poor. The blisters on my hand were aching but nothing truly life-threatening has happened. That morning there was a continued buildup of ice in our sleeping bags and our tent had collected so much ice inside it that it was getting difficult to stuff it in its storage bag. The icing of the inside of the tent was another interesting phenomenon of arctic travel. Water vapor from cooking, breathing, and warm bodies inside the tent froze on contact with the inner walls of the tent creating an icy layer that continually scaled off and fell inside the tent and collected on the floor. If it was warm enough inside the tent the ice on the floor would melt leaving puddles of water which constantly had to be mopped up to keep from getting everything wet. In order to combat this nuisance many cold-weather tents come fitted with a “frost liner”, a porous cloth liner for the inside of the tent that traps the ice and can then be taken outside and shaken out. The frost liner greatly helps the icing problem, but in the extreme temperatures we were experiencing, the ice build-up overwhelmed the system and ice was a constant problem, both in terms of weight build up and ongoing dampness inside the tent.

As we “mushed” our way along the coast we learned that, contrary to common belief, there isn’t a great deal of snow in the arctic. The temperatures are so low and the air so dry that there is very little snowfall;

Perhaps the most grinding, spiteful, vexing obstacle is the ever-present wind. At a still air temperature of -20F, the wind magnifies the cold and creates the “wind chill” effect of –60F.

As we cleared Booth Island and Booth Point, the weather improved.

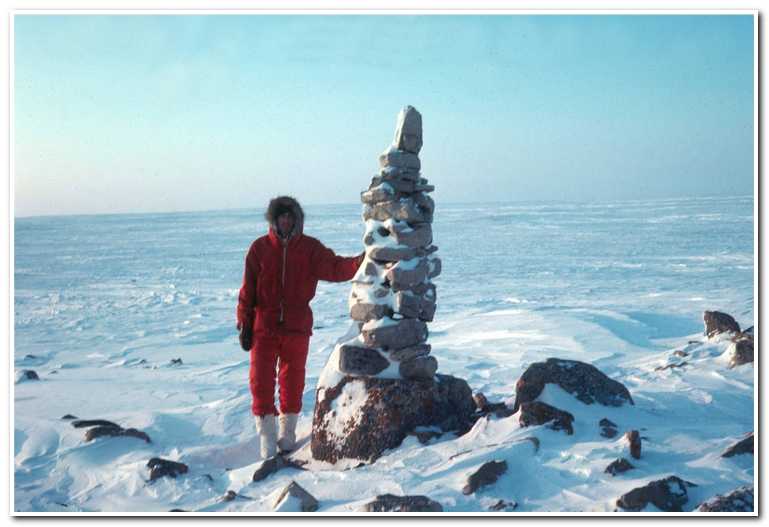

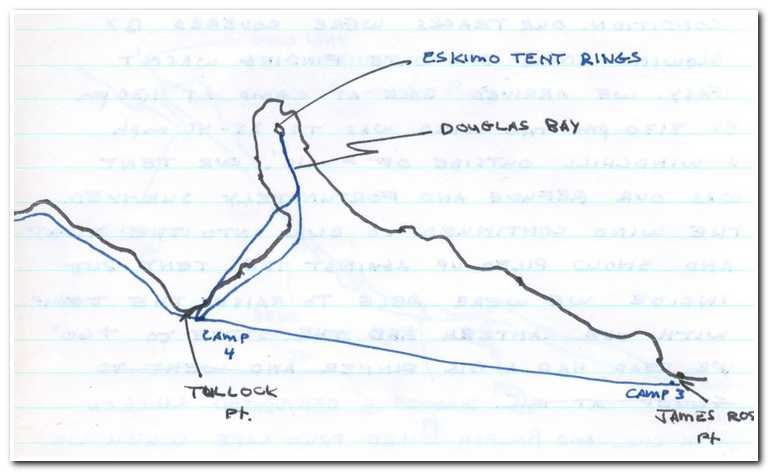

1:00 p.m. We stopped for lunch and another recharge of our internal furnaces. After lunch, it was time to move on to James Ross Point which was marked by an eight-foot-tall cairn. After rounding James Ross Point and coming to Douglas Bay the weather and ice conditions got even better.

6:30 p.m. Having put in a full day and making 11 miles we stopped and made camp. It seemed as though at long last a sustainable rhythm was developing and we were able to pull at about 1 ¾ – 2 mph,

While we were eating dinner, an Inuit trapper came along in the dark heading for Gjoa Haven. His Ski-doo was missing on one or more cylinders and it made a comical sputtering sound as it approached. The Inuit came to the tent and got quite a laugh out of the three Kabloonas camping and pulling a sled out in the middle of nowhere. He was very friendly and though he spoke no English pointed and laughed at Bill who was up sewing a hole in his pants. That sort of thing was strictly “women’s work” where he came from.

10:30 p.m. We finished the day with a hot cup of tea then turned in.

A pal’s last need is a thing to heed, so I swore I would

not fail;

And we started on at the streak of dawn; but God! He

looked ghastly pale.

He crouched on the sleigh, and he raved all day of his

home in Tennessee;

And before nightfall a corpse was all that was left of

Sam McGee.

March 28. We were all suffering minor frostbite to the fingers and nose.

There wasn’t a breath in that land of death, and I

hurried, horror driven,

With a corpse half hid that I couldn’t get rid, because

of a promise given;

It was lashed to the sleigh, and it seemed to say: “You

may tax your brawn and brains,

But you promised true, and it’s up to you to cremate

those last remains.

March 29; 6:30 a.m. Started the stove and lantern and made breakfast. The wind was down to 10 mph, –5F degrees, so we decided to take a rest day and explore Douglas Bay, taking a break from sled pulling.

9:00 a.m. Left camp. A short distance from

What a relief it was to hike along and just absorb the stark reality of where we were. The squeaking of the snow, with each step, was hypnotic as was watching the snow blown across the ice like a vast frozen Saharan sandscape. Even the discomfort of the frostbite and the ever present wind only seemed to add intensity to the feeling of being totally alive this morning.

10:00 a.m. After leaving Tullock Point the wind began to rise and the temperature started falling, but this only added to the enchantment of that morning’s explorations.

11:00 a.m. As we approached the far reach of Douglas Bay, we came upon a small islet with several tent rings built on it. The wind became stronger, 20 mph and the temperature dropped to –20F, creating a wind chill of –60F. We rested for about twenty minutes and speculated about the Inuit who had lived here. There were old Inuit stories about how native hunters and their families, living near here, had seen and spoken to Franklin’s retreating crews in this area during the spring of 1848. Unfortunately, the cold and rising winds cut short our musings on Franklin and we decided our own situation might tragically deteriorate if we didn’t get back to camp.

11:30 a.m. We left the islet and started back toward camp. The wind was now directly in our faces at 30 mph and the wind chill was more than –80F. Things were getting serious in a hurry! In addition to the cold, our outbound tracks were covered by the blowing snow and the winds were creating a ground blizzard of snow and ice crystals that made route finding, not only difficult but painful as well. Since it was impossible to follow our original route back to camp we veered to the west, using the snowdrift patterns as a makeshift natural compass, and walked until we intercepted the shoreline of the bay. The terrain was so flat and featureless that the only way we could tell when we had reached the shoreline was when we accidentally stepped in the hidden shoreline “tidal cracks”. Tidal cracks are another unique feature of the arctic. As the tide rises and falls the ice along with the shoreline breaks and forms area about twenty to thirty feet across of cracks and small crevasses which then get filled in and hidden by blowing snow. As a result, there is a “keep walking until you step in a hole” rule that applies to find the shoreline navigation in the arctic. Once we reached the land, we traveled, nearly blind in the blowing snow, walking parallel to the shore cracks until we reached the cairns at Tullock Point. From there we were able to locate our camp about one hundred yards distant. We reached camp, tired and stretched thin but high on having overcome the challenge that the arctic had thrown at our little band of arctic warriors. The hike back to camp stands out in my mind as the worst, most desperate hike I have ever undertaken but at the same time, one of the most satisfying.

3:30 p.m. By the time we reached camp the wind was blowing a constant 40 mph and the temperature had dropped to –25F (wind chill -110F). Dinner that night was two chicken with rice dinners each and a piece of our cherished heated bourbon-soaked fruitcake. The aroma of the fruitcake changed the entire complexion of the misery we had endured.

10:15 p.m. We finished off this surprisingly eventful day by chain reading a few more chapters of SHOGAN and turned in.

Now a promise made is a debt unpaid, and the trail has

its own stern code.

In the days to come, though my lips were dumb, in my

heart how I cursed that load.

In the long, long night, by the lone firelight, while the

huskies, round in a ring,

Howled out their woes to the homeless snows- Oh God!

how I loathed the thing.

March 30. The next morning dawned clear,

10:10 a.m. We left camp and leaned into the traces once again. The going was slow, 5 – 6 recitations/mile, because of, new deep snowdrifts across our route, causing our top-heavy sled to tip over, all too often. If spring weather is one of the joys of arctic travel then a capsized sled is surely the indomitable nemesis. In addition, we were pulling, as usual, into the wind.

1:00 p.m. We stopped,

5:05 p.m. We rounded Peglar Point and made camp near some fox traps about a mile past the point. A beautiful clear night –15F, ¾ moon, no wind. The sleeping bags were really getting icy and each night felt colder because of the dampness we slept in.

And every day that quiet clay seemed to heavy and

heavier grow;

And on I went, though the dogs were spent and the

grub was getting low;

The trail was bad, and I felt half mad, but I swore I

would not give in;

And I’d often sing to the hateful thing, and it

hearkened with a grin.

March 31; -35F; clear. We slept in till eight and began the routine work of boiling water and eating yet another dehydrated meal. We planned to pull to the DEW Line station at Gladman Point that day; one last hard long day of leaning into our harnesses dragging the sled along before a well-deserved rest in the warmth of the station.

10:00 a.m. We packed up camp and started out.

Once we left the ice and started up the hill the going was nearly impossible. 2’ to 3’ deep snow with a breakable crust. We broke through the crusted snow with each step and went in up to our knees. Getting any traction to pull the sled was nearly impossible. The work was so exhausting that every one hundred feet or so it was necessary to stop and rest before pushing on. In addition one or the other of the sled’s runners was regularly breaking through the snow causing the sled to capsize onto its side. It took 2 hours of Sisyphean labor to pull the sled less then ½ mile to the top of the hill.

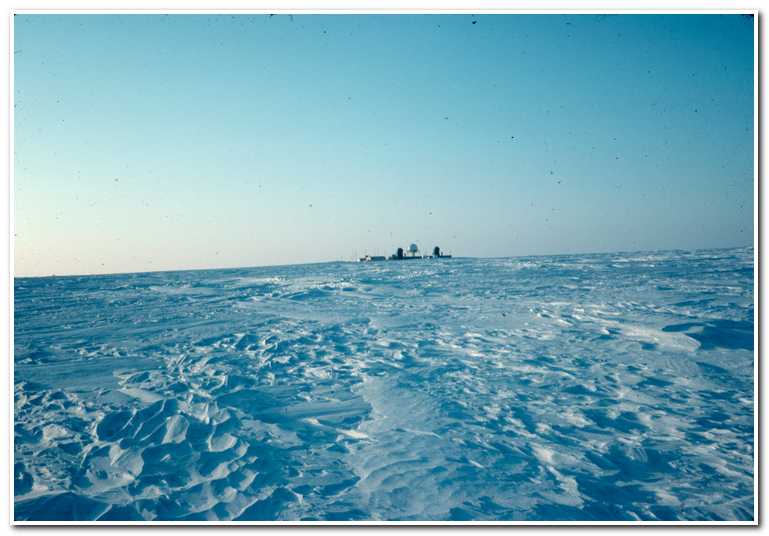

7:15 p.m. We were exhausted, but we had made it and at last stood at the door of the DEW Line station (designated in military jargon “CAM – 2”, for Cambridge Bay Station 2). These Radar stations were built in the 1950s to serve as a northern tier defensive shield to sound the alarm should the Russians decide to launch an attack on the United States. They were phased out in the 1980s as more advanced technology took their place.

Now an awkward situation arose. How could we prove to the military personnel at the station that we weren’t Russian agents, or at the least union organizers? I probably didn’t help matters when asked by the station commander what we were doing on their doorstep, I laughingly responded to what I thought was a silly question “selling magazine subscriptions”. Our would-be host failed to see the humor in this and asked his question once again. Did we have some ID. Driver’s License? Social Security card? Credit card? Any ID? All the hours of planning and preparation for this trip and none of us had thought of this contingency. “No”, (short and sweet, no attempt at humor) we said. None of us thought we would need our wallets while man hauling a sled across the arctic and had left them behind in Cambridge Bay with Ken Murphy. Finally, Bill (aka “Sweet Old Bill”, or sometimes just the initials) broke the impasse and remembered his World War II navy serial number, Al his Boeing security ID number, but all I could offer up as proof of who I was, was my social security number.

We were ordered to wait in an isolated room off the living quarters of the base, while the commander, Ray Newell, telexed NORAD command in Boulder Colorado and found that we were all innocent pilgrims on a crazy journey and allowed temporary security clearances to stay as guests at the station. We were warned, however, to roam only around the living quarters and not to try to enter the radar domes or control room. DEW Line stations were still considered secret military installations and visitors were not encouraged.

Once the formalities were taken care of our first order of business was a warm shower and a clean change of clothes. After cleaning up we descended on the kitchen to gorge on hot buttered toast. Now buttered toast may be good and all that but, why was that the first thing we all unanimously craved? What we came to understand was that it wasn’t the toast, per se, but the slabs of melted butter that our bodies were demanding to replace all those fat calories we had burned pulling the sled and keeping warm. After we had gorged ourselves on toast we wolfed down a big meal of real food, steak, and potatoes. Those boys on the DEW Line knew how to put on the feedbag. As we ate “Spud”, the cook, regaled us with stories from the DEW Line. My favorite was about the polar that broke through the kitchen window and got stuck half in and half out but nonetheless determined to get inside. Spud fended him off by tossing loaves of bread to the hapless bear until he could finally be scared off. As Spud put it “I kept on tossin’, and he kept eatin’.”

After our “adventures with Spud” we watched “Macon County Line,” an early 60’s teenage Bonnie and Clyde movie, and then turned in, to a real bed with sheets and covers and a good night’s sleep.

TILL I CAME TO THE MARGE OF LAKE LEBARGE,

AND A DERELICT THERE LAY;

IT WAS JAMMED IN THE ICE, BUT I SAW IN A TRICE IT WAS

CALLED THE “ALICE MAY.”

AND I LOOKED AT IT, AND I THOUGHT A BIT, AND I LOOKED AT

MY FROZEN CHUM;

THEN “HERE,” SAID I, WITH A SUDDEN CRY,

“IS MY CREMA-TOR-EUM.”

April 1, 8:00 a.m. We had a hardy breakfast.

1:00 p.m. It was –30F with a wind chill of –40F, the skies were crystal clear and we were eager to go find the cairn left by Thomas Simpson in 1838. After pulling for three hours in the traces we made Cape Herschel. A more desolate, uninviting place would be hard to imagine but it had an aura of inescapable history to it. Somehow we were all now a part of that history.

.

We made camp near a pressure ridge of shore ice and read and

enjoyed the warmth of dry sleeping bags and warm soup.

.

Some planks I tore from the cabin floor, and I lit the

boiler fire;

Some coal I found that was lying around, and I heaped

the fuel higher;

The flames just soared, and the furnace roared—such

a blaze you seldom see;

And I burrowed a hole in the glowing coal, and I

stuffed in Sam McGee.

Then I made a hike, for I didn’t like to hear him sizzle

so;

And the heavens scowled, and the huskies howled, and

the wind began to blow.

It was icy cold, but the hot sweat rolled down my

cheeks, and I don’t know why;

And the greasy smoke in an inky cloak went streaking

down the sky.

.

April 2. We were eager to

I do not know how long in the snow I wrestled with

grisly fear;

But the stars came out and they danced about ere again

I ventured near;

I was sick with dread, but I bravely said: “I’ll just

take a peep inside.

I guess he’s cooked, and it’s time I looked;”….

then the door I opened wide.

And there sat Sam, looking cool and calm, in the heart

of the furnace roar;

And he wore a smile you could see a mile, and he said:

“Please close that door.

It’s fine in here, but I greatly fear you’ll let in the cold

and storm–

Since I left Plumtree, down in Tennessee, it’s the first

time I’ve been warm.”

April 3 The day was calm and clear,

There are strange things done in the midnight sun

By the men who moil for gold;

The Arctic trails have their secret tales

That would make your blood run cold;

The Northern Lights have seen queer sights,

But the queerest they ever did see

Was that night on the marge of Lake Lebarge,

I cremated Sam McGee.

April 4. We packed for the last time,

On arriving back at the DEW Line station we were told of a big polar bear coming through the station that morning from the direction of Cape Herschel! We hadn’t seen the bear and I think we were all a little disappointed that that experience would have to wait until another time.

We had heeded the call of the wild and would return again and again over the next two decades to the arctic. Our understanding and appreciation of it would grow but never be complete, and that is what made it so compelling.

There are strange things done in the midnight sun,

By the men who moil for gold;

The Arctic trails have their secret tales

That would make your blood run cold;

The Northern Lights have seen queer sights,

But the queerest they ever did see

Was that time on shores of King William Island

I did go; my friends and me.