Northern Ellesmere Island

Expedition of 1980

1980 Northern Ellesmere Island Expedition Team

(left to right; Dave Adams, Al Errington, Marty Waller, Brad Albro, Steve Trafton, Don Goodman, Bill Davis)

Dave Adams

Al Errington

Marty Waller

Brad Albro

Steve Trafton

Don Goodman

Bill Davis

The wild is calling…..let us go.

Robert Service

Once again I find myself gazing out my library window at the wind whipped waters of Puget Sound. On this cold, rainy northwest winter’s afternoon my mind drifts to thoughts of new adventures; hiking or climbing in a distant mountain range or kayaking some challenging new long distance route. While many people tend to focus on the past it has always seemed to me to be more natural and fulfilling to look forward to the next unknown and new challenge. That being said from time to time I can’t help but take a contemplative pleasure in reliving past challenges and adventures. On this occasion, as on so many others, my impromptu walk down memory lane leads me back to the high arctic.

When my climbing partner, Al Errington and I undertook our first arctic expedition in 1977 we were looking for a challenge. While we both had a substantial resume of climbing and hiking experience we hoped that the arctic would prove to be unique in our catalog of wilderness experiences and would allow us the opportunity to be tested physically and mentally. Little did we foresee the long term relationship that would grow out of those first steps across the arctic wilderness.

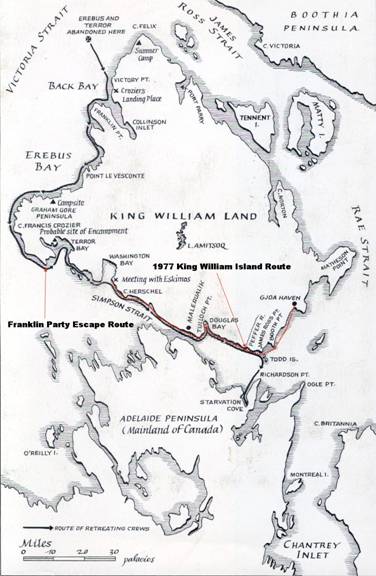

In the early spring of 1977 Al and I, along with Bill Dougall, a fellow Seattle Mountain Rescue member, man-hauled our homemade, unbalanced, top-heavy sled around the southern coastline of King William Island.

We were not only interested in getting experience in extreme cold weather travel but, also searching for cairns and artifacts that might have been left behind by early British expeditions in search of the Northwest Passage, during the early-mid 1800s. It was along this desolate shoreline that the famous expedition, commanded by Sir John Franklin, struggled to reach safety, after abandoning their ships, the Erebus and Terror. Franklin’s ships had become hopelessly beset in the pack ice off the northwest coast of King William Island and the expedition’s only hope for survival was to travel south, half way around King William Island, across Chantrey Inlet and up the Back River in hopes of reaching safety at Fort Reliance or Fort Resolution on Great Slave Lake or along the western shores of Hudson’s Bay. Franklin’s crews never made it. All one hundred twenty-nine hands were lost.

When nothing was heard from the expedition after three years the Admiralty sent out numerous expeditions that sought to unravel the mystery and the fate of the lost Franklin expedition. It was discovered that the doomed explorers died of scurvy, exhaustion and exposure during their desperate attempt to reach safety. Though the fate of the expedition has long been known, an aura of mystery still surrounds the expedition and serves to peak the interest of modern-day arctic historians and adventurers who try to detail the last days of those brave souls who first trod those distant shores.

During our effort, we learned firsthand just what a harsh unrelenting and unforgiving challenge the arctic can be. We endured continual temperatures of -50F and wind chills of -100F were not uncommon. In addition we learned that man hauling sleds across the sea ice was amongst the most strenuous exercise ever devised. It soon became obvious, after our first hand experience that the men of the Franklin expedition didn’t stand a chance of making it to safety in their scurvy ridden and starving condition. In this extreme environment we got an introduction to arctic travel and self sufficiency that would not soon be forgotten. As Robert Service said in “The Cremation of Sam McGee,” “it wasn’t much fun.” But it had, in some unexplainable way, rather than scaring us off, only whetted our appetite for more.

110 below wind chill in Douglas Bay, King William Island

After that first trip to King William Island we were convinced that the arctic held the promise, not only of challenge but also of many indelible life experiences. The North had got us.

A year later Al and I decided to explore one of the many unexplored and unclimbed mountain ranges that make up a large portion of the high arctic. So in April of 1978 we organized and led a group of our local Mountain Rescue friends to the north coast of Baffin Island.

While on this expedition we traveled about seventy miles by Inuit komatik (sled) from the village of Clyde River to Sam Ford Fiord. We were one of the first expeditions into this remote and spectacular area. During this trip Al and I made the first ascent of Broad Peak, a granite monolith that rose over 6100 feet vertically out of the frozen fiord (nearly twice the free standing height of El Capitan in Yosemite Valley). We spent three weeks exploring the area, endured a multi-day storm and narrowly escaped with our lives after being caught in a huge slab snow avalanche.

Broad Peak, Sam Ford Fiord

In 1979 Al and I along with Bill Dougall once again headed north. This time it was to Iceland, to cross country ski across the huge Vatnajokull Glacier, the largest in Europe.

After this cross country skiing and sled pulling trip we spent several weeks climbing and then traveling around the country. We drove from Husavik and Akureyri along the north coast to Dorsmork near the south coast, camping along the way and just generally having fun exploring the countryside. We also spent time swapping war stories with members of the Icelandic mountain rescue group (the Flugbjorgunarsveitin) While the traveling wasn’t as arduous, dangerous, or remote as on the Baffin and King William trips the geology and unique character of Iceland held its own drama.

Climbing in Iceland 1979

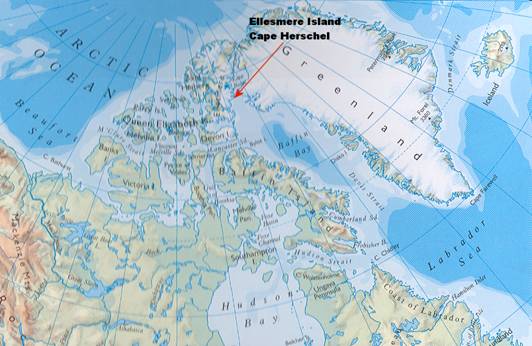

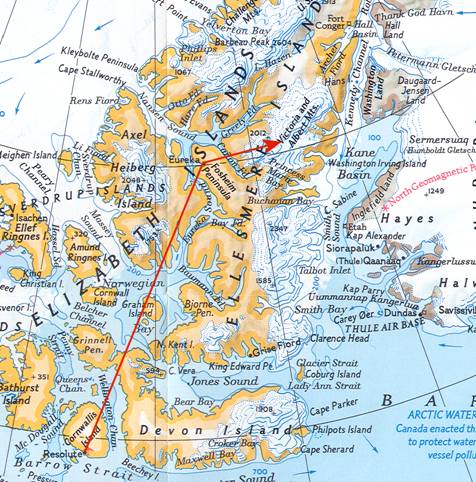

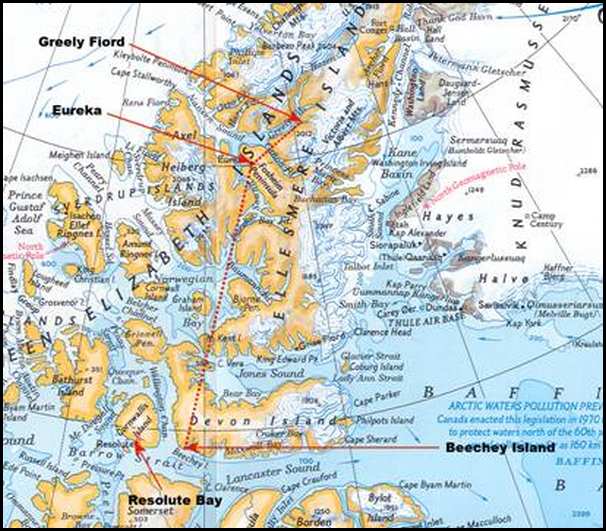

After this diverse trio of arctic trips Al and I decided to undertake a major climbing and arctic exploration venture even further north and even more remote then our prior trips. This time we planned to fly to Resolute Bay (74 41N, 94 49W) on Cornwallis Island (new Inuit name Qausuittuq). From there we would fly north, beyond the North Magnetic Pole, in a chartered De Havilland Twin Otter equipped with skis and be dropped off at Cape Herschel (78 41N, 75 01 W), on the east coast of Ellesmere Island, about 640 nautical miles from the north pole and then pull our sleds west across the island, climbing as we went through several remote mountain ranges and eventually descend out of the mountains, near Lake Hazen and there we would be picked up by the Twin Otter for our return to Resolute Bay.

Because of the scope and the remoteness of the expedition the team members selected to go with Al and I would have to be self sufficient and competent in the mountains and possess a good expedition temperament (easy going, adaptive, focused on the objective). We decided to give first priority to members of our 1978 Baffin Island expedition since they had all been well trained and tested by the harsh and sometimes dangerous conditions found in arctic mountaineering. Boeing engineer Marty Waller 46, along with Bremerton businessman Brad Albro 31, had served their arctic apprenticeship on Baffin and were welcomed aboard. How could we say no to anyone who had survived the great Baffin avalanche of 1978? To fill the remainder of our expedition roster we enlisted arctic “first timers” Don Goodman 23, Dave Adams 24, and Bill Davis 37, all members of Seattle Mountain Rescue. So it was that in mid May of 1980 the seven of us, filled with visions of daring do, embarked on our grand high arctic adventure. The wild was calling us.

1980

NORTHERN ELLESMERE Island Expedition

The Ballad of Yukon Jake

By Ted Parmentier

Oh, the North Country is a hard countree

That mothers a bloody brood;

And its icy arms hold hidden charms

For the greedy, the sinful and lewd,

And strong men rust from the gold and lust

That sears the Northland’s soul;

But the wickedest born, from the Pole to the Horn,

Is the Hermit of Sharktooth Shoal.

Late 1979 – April 1980 – Every expedition to remote areas, requires a lot of planning. Food and equipment need to be decided on, gathered together and packed for transport to the field. Personnel need to be chosen and responsibilities assigned to the team members. Transportation needs to be arranged to and from the expedition objective. In the months leading up, departure maps need to be consulted and routes roughed out so that the team has some advance idea of what the objectives of the expedition will be as well as how the leaders plan to accomplish those objectives. The lion’s share of this planning falls to the expedition leaders, in this case Al and I.

Al took on the job of identifying and gathering together all the group gear we would need: tents for shelter, sleds and cross country skis for traveling, and climbing equipment for three rope teams. My responsibility was for the logistics of the expedition: air travel to and from Resolute Bay, Twin Otter charter for the last leg of the trip into the mountains, food menus, maps and coordination with the Canadian authorities whose help would be necessary to get to and from Northern Ellesmere Island. This is just a short list of the hundreds of details that arise in the planning of a major expedition. Our team needed to be completely self-sufficient and capable of surviving in the remote arctic at 80 degrees north for at least three weeks so as much pre-planning and anticipation of problems needed to be identified and prepared for ahead of time.

By April of 1980 most of the pre-planning and logistical issues had been dealt with and our team was ready to start packing all of our food and equipment in preparation for transport to our objective. The packaging of food supplies and crating of all the group equipment is the first time that all the expedition members get to work together as a team. Usually this packing is undertaken in someone’s basement or in a warehouse and inevitably it turns into an impromptu party as the expedition finally leaves the abstract “drawing board” and begins to take on a physical reality. During these “packing parties” expedition members get to share stories of past expeditions and contemplate the challenges that will be uncovered in the current effort. New members were regaled by the “old timers” with the excited and sometimes slightly exaggerated stories of our earlier trips that we hoped would infect them with the “Arctic Fever”. The Fever would serve to drive the expedition forward during the dull and trying times that would surely arise during the trip.

Our food supplies were sorted into six different daily menus, with a breakfast, lunch, dinner and trail snack for each of the seven expedition members. These daily rations were then packed into five gallon pressed lid cans which were indexed and labeled for distribution in the field.

Al had the responsibility of supplying the expedition with sleds, and for this effort he decided that individual toboggan-type sleds would be preferable to the big team harnessed sled we had used on King William Island and Baffin Island. These sleds would be loaded with each expedition member’s personal gear as well as his one seventh share of the group equipment. The sleds were designed to be used with cross-country skis and for travel over snowfields and glaciers rather than the flat sea ice of previous trips.

During the first week of May this sorting and packing process was completed and all our food, climbing equipment, tents, sleeping bags and sleds were crated and likewise inventoried for shipment north. When we were done we had nearly 800 pounds of food and group equipment and seven eager latter day arctic explorers ready for whatever lay ahead.

Organizing and packing food and supplies

Now Jacob Kaime was the Hermit’s name,

In the days of his pious youth,

Ere he cast a smirch on the Baptist Church

By betraying a girl named Ruth.

But now men quake at Yukon Jake,

The Hermit of Sharktooth Shoal;

For that is the name that Jacob Kaime

Is known by from Nome to the Pole;

He was just a boy and the parson’s joy

Ere he fell for the gold and the muck,

And he learned to pray’ mid the hogs and hay

On a farm near Keokuk.

May 13, 1980. On this cool spring morning the members of the 1980 Northern Ellesmere Island Expedition loaded our gear into Brad’s Jeep Grand Cherokee and Al’s Toyota Landcrusier and headed for the Vancouver B.C. airport and the starting point of our journey north. After an uneventful crossing of the border at Blaine we arrived at the airport about one o’clock that afternoon and began the lengthy process of checking our fourteen pieces of baggage aboard the Pacific Western flight to Edmonton, Alberta, where we were scheduled to catch the twice a week flight to Yellowknife and Resolute Bay. Fortunately I had contacted Pacific Western several weeks in advance of our departure and they were very helpful in accommodating our obviously excess and oversize baggage at no extra charge. Fortunately for us the early 1980’s were still a time when expeditions to the far north still caught the imagination of airline employees and government officials and so logistical bottlenecks and bureaucracies that would be nearly impossible to surmount today melted away in respect of our unusual objectives and their “Walter Mittyism.”

The flight to Edmonton was uneventful but for the urgent trips to the restroom by several of the team members who were suffering from Giardia infestation acquired on a recent climbing trip in the Cascade Mountains. Giardia, the ban of all wilderness travelers is caused by a micro organism common in wild animal intestines. Drinking water contaminated by Giardia causes painful and urgent diarrhea and requires treatment with powerful antimicrobial drugs that most often leave the patient nearly incapacitated for several days to a week (thus the adage, always drink upstream from the herd).

We arrived in Edmonton around six that evening and stored our baggage at the Pacific Western warehouse at the airport. After securing our gear we rented a small compact car, somehow managed to pack all seven of us in, and headed to the nearest motel to get rooms for the night. After checking in to the motel we drove into town and had a feast of pizza and beer in celebration of our first day together as a team (although with this group it didn’t really take a reason to party at the local pub).

May 14, 1980. Despite the pre-expedition party the night before every Giardia infested, beer soaked body was up by 5:00 a.m. I drove Marty, Bill and Brad to the airport to retrieve and check in our baggage, then back to the motel to pick up Al, Don and Dave. By a little after six everyone was at the airport, the baggage was checked, and we were able to have a light breakfast before our departure at 7:30 a.m. The one and a half hour flight to Yellowknife was interesting because we were able see, from 33,000 feet, the transition from the northern Rocky Mountains west of Edmonton, to the rolling foot hill region around the Peace River Valley. We also got a good look at Lake Athabasca and the Caribou Mountains before reaching Great Slave Lake. By 9:30 a.m. we had landed at Yellowknife, at about 62 degrees north located on an inlet on the north shore of the lake. We had a short wait in Yellowknife while last minute cargo was loaded and the pilots confirmed that the weather in Resolute Bay was good enough for the approach and landing on the somewhat primitive ice and gravel runway.

The plane we flew on from to Resolute Bay was a dual purpose 727. The plane had a normal cargo hold but, in addition, the passenger compartment was convertible to cargo area by removing any unneeded seats and loading the empty space with cargo containers through a 10’ x 10’ cargo door forward of the wing on the port side of the plane. This configuration allowed the airline to maximize the cargo/passenger mix on each flight. By 10:40 we were airborne again, seated behind several tons of stowed cargo, on the last leg of our approach journey to the high arctic.

Dual purpose 727 for Arctic passenger and cargo service

During the two hour flight over northern Canada and out over the Arctic Ocean, we flew across Victoria Island, Prince of Wales Island and finally on to Resolute Bay on Cornwallis Island. I couldn’t help but be impressed by those early explorers who first came here by sailing ship form Europe. The expanse of the Arctic, Lake Athabasca, is so much larger “in person” than can ever be adequately communicated while comfortably sitting in one’s living room. The vision out the window was one of flat tundra, littered with countless lakes, streams and rivers that stretch from horizon to horizon for a thousand miles. Just north of Yellowknife the snowline was crossed and gradually the dirty green-tan tundra evolved into a sheet of white dotted with the outlines of lakes and rivers. Finally we reached the shore of the Arctic Ocean and the view changed to one of an endless sheet of ice, rift with fracture lines and pressure ridges, punctuated by the outlines of remote and desolate looking arctic islands. It is not difficult at all to see how men were drawn here by the mystery of this inhospitable place. But, it is just as easy to see how tenuous survival would have been and how difficult any successful search or rescue effort would have been during the “golden age” of Arctic exploration in the 1800’s.

Resolute Bay Airport Terminal, 74 degrees north

We landed on the frozen gravel runway at Resolute Bay, at 74 degrees north, a little after one that afternoon and were met by employees of the Polar Continental Shelf Project (PCSP), our official Canadian sponsors, who had brought a truck to the passenger terminal to haul our gear over to the PCSP compound about a quarter of a mile away. The PCSP acts as the Canadian Government’s umbrella agency for all scientific research undertaken in the Canadian Arctic. Their help was vital in securing temporary lodging in Resolute, Twin Otter charter under their government discounted rate, white gas for our camp stoves, and radio communication. Without them the logistical and cost considerations in traveling the last four hundred miles to northern Ellesmere Island would have made the expedition impossible. We met our host, Frank Hunt, the PCSP Base Manager, and he assigned us to our temporary quarters in one of the bunk houses. These bunk houses were actually house trailers joined end to end, creating a long narrow rectangular structure divided into individual 7 x 10 foot rooms furnished with a surplus military bed. The bathroom facilities and showers were located at the end of each trailer unit. A central dining hall served all the guests and the food service was hardy, if not a gourmand treat. All in all it was a much more comfortable housing situation then we had imagined being located in such a remote environment.

Al sorting gear in the “bunkhouse”

After settling into our temporary quarters Al and I walked over to the Bradley Aviation hanger to meet our charter pilots and confirmed our proposed departure time the following afternoon. The weather report from the station at Eureka (79 59N 56 10W), on the west coast of northern Ellesmere Island, was good and expected to remain mostly clear for the next few days. This is great news, for as we had learned on past trips, travel in the arctic is dependent on the weather and delays are common while waiting for the weather to be flyable. We arranged to load the plane about noon the next day and be on our way around 1:30 p.m. This would put us on the ice at Cape Herschel by four or five o’clock, early enough to set up camp and sort gear before dinner.

Later that afternoon Marty and I drove into the Inuit village, about four miles from the airport, to buy cheese and butter and a few other last minute provisions. While in the village I located an old Inuit woman who agreed to make a pair of sealskin overmitts for me while I was in the mountains. We returned to the PCSP camp, had a big dinner in the mess hall and then worked on the sleds and further sorting of our climbing gear until about 9:30. The skies were clear and the temperature +5 degrees. The cold feels good after the 70 to 80 degree weather I had been experiencing in New York City while working for an investment banking firm on Wall Street. We turned in at midnight, still sunny outside!

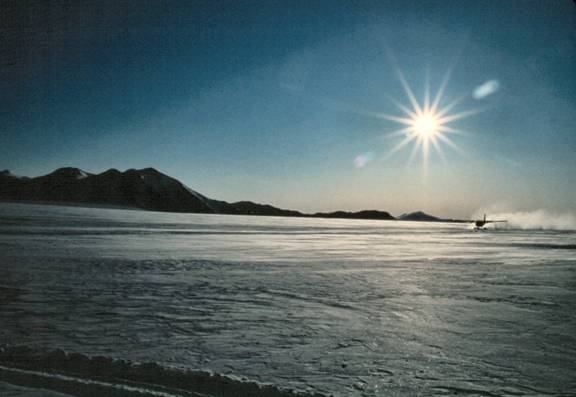

A “Hercules” preparing to take off at midnight from the ice covered runway at Resolute Bay

May 15, 1980. The team was up and at breakfast by about 8:00 a.m. the next morning, eagerly anticipating our Twin Otter flight north. After breakfast I checked in with our pilot, Dave Ray, about landing off the end of the Leffert Glacier rather than at Cape Herschel. Dave told us that a group had left earlier for Cape Herschel but had been forced back by fog. The weather all around Cape Herschel was a “no go”. There was an east wind off Greenland which was blowing across Baffin Bay and creating a massive fog bank in the Kane Basin and all along the central eastern coast of Ellesmere Island. We would have to wait until tomorrow to see conditions improved. The good news was that the barometer was rising so maybe the weather would improve.

Later that afternoon Marty, Brad and I learned about a “club” in town; The Arctic Circle Club, and walked over for a beer. The rest of the team joined us a few hours later and we ended up having dinner and a few more beers before finally leaving about midnight.

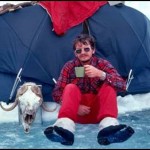

Unidentified member of the expedition practicing “Safe Sex” Arctic Style

May 16, 1980. In spite of the heavy partying last night we were all up by seven the next morning, had breakfast, and then went back to sleep. Everyone was up again at ten and we went over to Bradley Aviation for another confab. I wanted to ask the pilot’s opinion about an alternative plan I had come up with the day before just in case the weather at Cape Herschel was still bad. My new idea was to fly to the Mer de Glas Agassiz ice field and explore and climb in the Victoria and Albert Mountains a little above 80 north. We would gradually work our way from west to east across the Mer de Glas Agassiz and then descend the d’Iberville glacier to Greely Fiord. There we would spend a few days exploring the fiord before the Twin Otter would return to pick us up for the return trip to Resolute Bay. The team agreed that this alternative sounded like a good one. Our pilot said that the weather in the Victoria and Albert mountains was good and that if we wanted to we could leave around 7:00 p.m.

7:00 p.m. and we got word that the weather on the Mer de Glass Agassiz was broken clouds with moderate winds and a temperature of about zero. It was a go! Sometimes things happen fast in the Arctic. After a lot of waiting, suddenly action! It took about half an hour to load all our gear into the Twin Otter, we said our last goodbyes and we were off!

Loading our gear in the ski equipped Twin Otter for the flight to Eureka and the Mer de Glace Agassiz

For the first hundred miles the visibility was good and we had great views of Cornwallis Island and the frozen ocean to the north, then we flew into a cloud bank and near zero visibility for the next hundred miles until we broke out again about 45 minutes from Eureka. We were rewarded with views of Axel Heiberg Island to the west, icebergs in the frozen fiords beneath us, and Ellesmere Island to the east. We were, of course, well north of the north magnetic pole so the standard magnetic compass was useless for navigation. In addition, 1980 was well before GPS navigation existed so our pilots relied on a World War Two vintage astro-compass for navigation.

Astro-compass mounted on the instrument panel of the Twin Otter

Every ten minutes or so, if it wasn’t too overcast, the co-pilot would take a “sun shot,” do his calculations to derive our position. As antiquated as this navigation system was, we soon had the Eureka weather station landing strip in sight and ten minutes later we were on the ground at 80 North, only 600 nautical miles from the North Pole.

At Eureka we refueled the airplane from fifty-five gallon drums of aviation fuel cached beside the runway. During the refueling process the pilot shut down only the port side engine on the Twin Otter and kept the starboard engine running. He told us that in such remote areas of the arctic this was standard practice. There are two reasons for this procedure. One, by keeping the starboard side engine running it would provide heat to the aircraft and to the idle port side engine. This would keep the cockpit instruments and port side engine from freezing up during refueling. Two, if for some reason the port side engine wouldn’t restart the pilot would have at least one engine to fly back home on.

Refueling the Twin Otter at Eureka, 80 North.

Note the starboard engine still running as a safety precaution.

After refueling in Eureka we took off on the last leg of our trip into the mountains. As we flew along the plateaus south of Greely Fiord we could see musk ox tracks and occasionally a group of musk ox huddled together in defense against the frigid winds that were starting to blow harder at the low elevations along the fiord. We finally left the hills and plateaus behind and entered the western edge of the Victoria and Albert mountain range set amid the massive Mer de Glas Agassiz ice cap (the Mer de Glas). We were rewarded with a clear view of the broad ice cap, punctuated by scores of unnamed, unclimbed peaks. It was incredible!!

Route from Resolute Bay to Victoria and Albert Mountains

At about 12:30 a.m. we picked out a spot on the vast expanse of the western edge of the Mer de Glas, lowered the skis on the plane and landed on the glacier. After landing, the pilot took one last astro-compass reading and told us we were at 80 10N, 76 45 W, give or take three to five miles (as it later turned out, we were actually at 80 10.0N, 76 35.0W, only 1.5 – 2 miles from our astro-compass estimate).

After landing in the Victoria and Albert Mountains our pilot takes an astro-compass reading to give us an approximate position for Camp 1.

Unloading Twin Otter at Camp 1, 12:30 a.m.

The sun was high in the sky and the wind was at about 5 knots. We quickly unloaded the plane and watched as the Twin Otter, engines at full throttle, roared down the glacier and lifted off.

Twin Otter taking off from the Mer de Glace Agassiz.

But a service tale of illicit kale

And whiskey and women wild,

Drained the morals clean as a soup tureen

From this poor but honest child.

He longed for the bite of a Yukon night

And the Northern-lights’ weird flicker,

Or a game of stud in the frozen mud

And the taste of raw red likker.

He wanted to mush along in the slush,

With a team of huskie hounds,

And to fire his gat at a beaver hat,

And knock it out of bounds.

The plane’s turbine engines echoed their high pitched drone off the rocky mountain walls that surrounded our landing site as the pilots turned and buzzed our campsite and gave a farewell rocking of their wingtips.

One last farewell rock of the wingtips

and the Twin Otter was gone; then

SILENCE

Not just quiet, like the rustling of leaves in a forest, or the light lapping of water at a lake shore, but rather the complete lack of any sound. It is strange but each time I am in the arctic outback, I am always most impressed with this unnatural absence of sound. Because the ears have nothing to hear all my sensory input is focused on the visual stimulation of the huge scope and beauty of the arctic. This focus makes the first moments, of this arctic immersion, an emotional as well as a sensory experience. This primal feeling is clearly imbedded in my memory and probably is the source of my “arctic fever.”

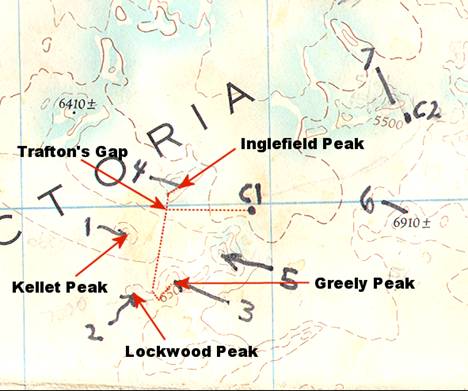

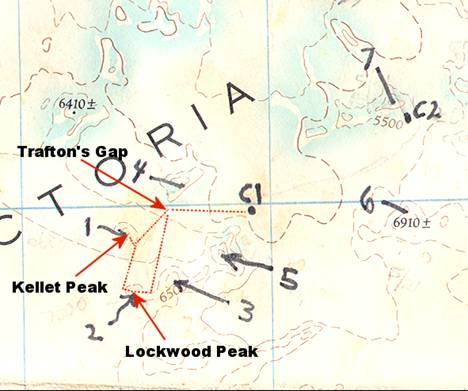

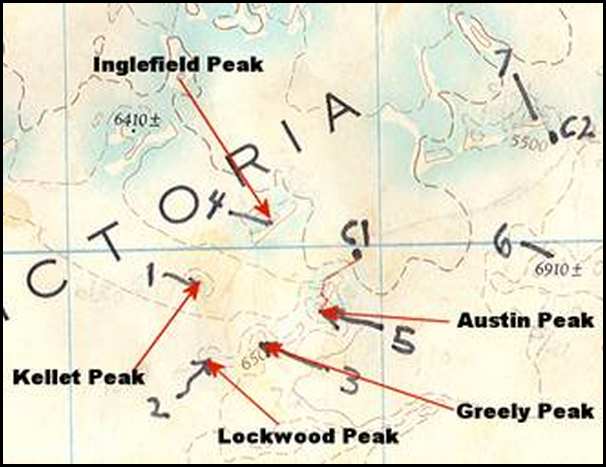

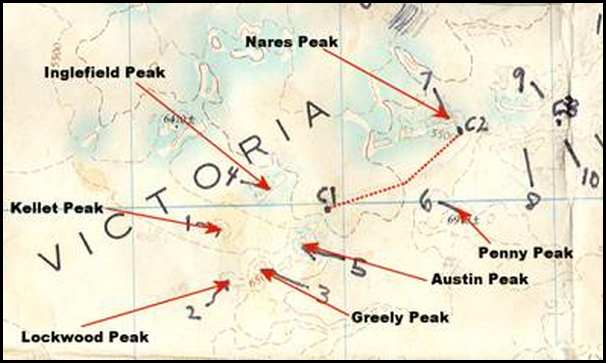

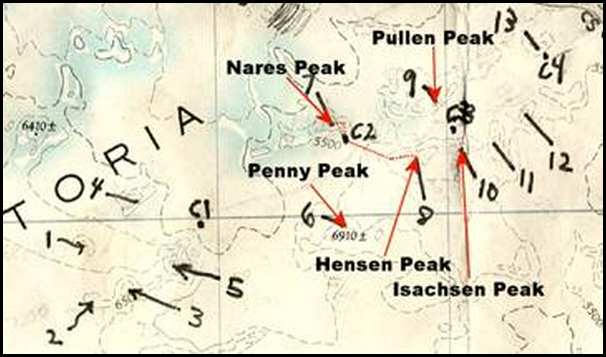

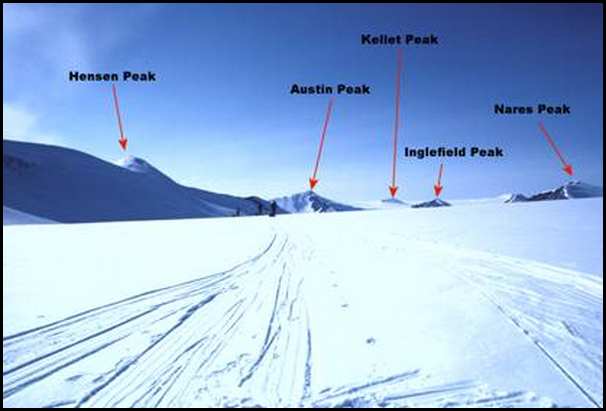

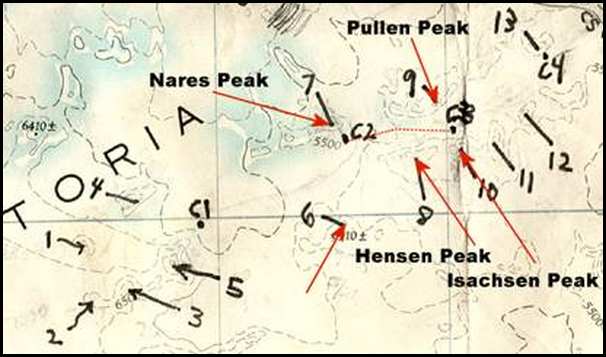

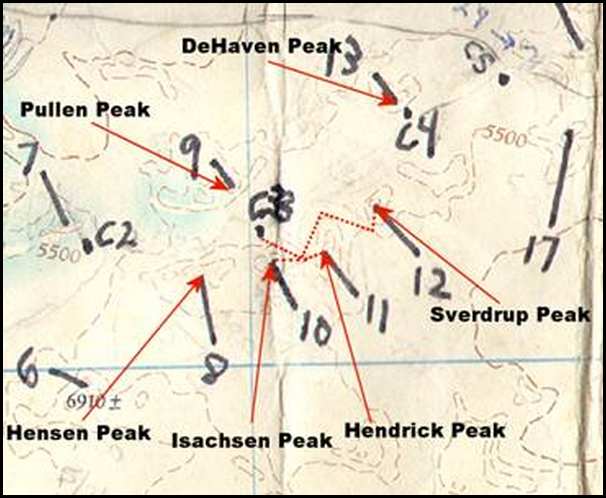

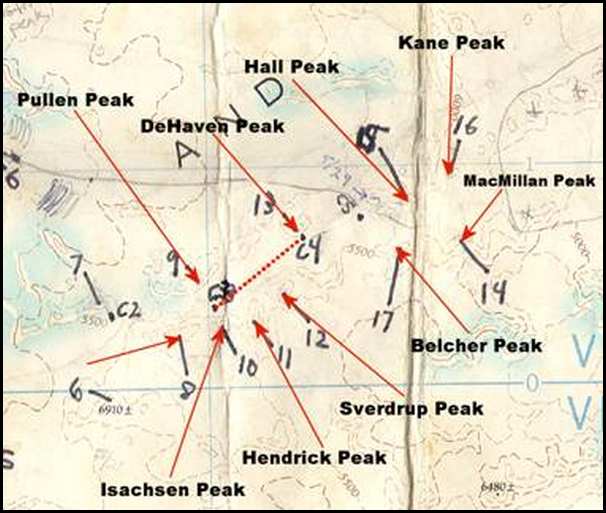

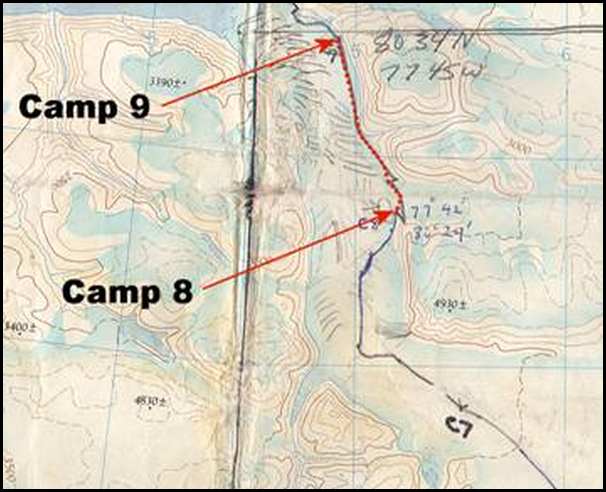

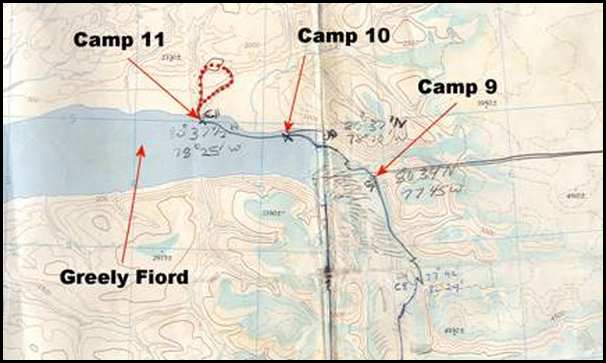

Original field map showing position of Camps and mountains in the Victoria and Albert Range.

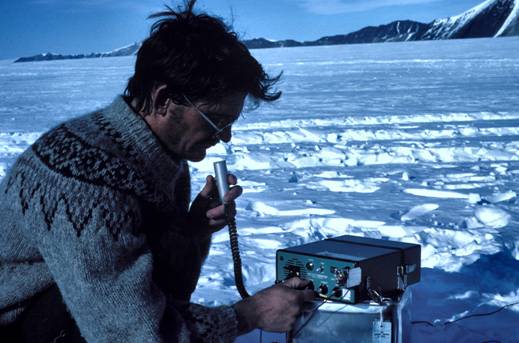

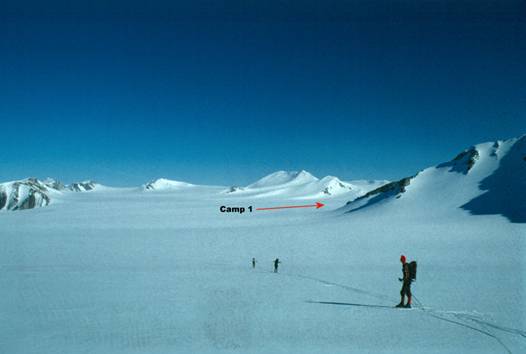

After this initial rush of awe and excitement at being in an unexplored area, surrounded by a whole range of unclimbed mountains ebbed, we set about establishing Camp 1 at 4800 feet. We tramped down a large snow platform, pitched our three tents, set up our long range single sideband radio and checked in with Frank Hunt back at Resolute Bay. A little after three in the morning we turned-in after a long day. The next day we planned on trying to pinpoint our location more accurately by checking the detail on the map with the position of the mountains around us. While it really didn’t matter much right then what our exact location was, in two weeks we would need to find the exit off the Mer de Glas to the d’Iberville Glacier in order to make our exit to Greely Fiord. At that point we would need to know exactly where we were.

Camp 1, Austin Peak on left, Kellet Peak

and Trafton’s Gap in the right background

May 17, 1980. I got up at 7:00 a.m. for the morning “sked”, the scheduled radio check in by each of the expeditions in the field sponsored by PCSP. These skeds were held at 7:00 a.m. and 7:00 p.m. During the sked each camp was called in turn and gave the current weather at their location and gave or received any messages for the “outside”. The skeds also served a safety purpose as well. If any group missed three skeds in a row without prior notification the Resolute Base would start a search and rescue operation.

After the sked I crawled back into my sleeping bag and dozed until nearly 11:00 a.m. when we all got up and started breakfast. The weather was clear and a balmy +23 degrees. Our plan was to cross-country ski over to the nearest mountains, with hopes of climbing two peaks before dinner.

The “Sked”

The “sked” was our single-sideband radio capable of radioing over 360 nautical miles between our campsite and Resolute Bay. The snow conditions were perfect and the scenery was inspiring to say the least. The only photography possible was with a wide angle lens because of the scope of the landscape around us. Even then it was not possible to capture the enveloping sense of remoteness and scope of the scenes before us. We skied for about two hours before coming to a col (circa 5200 feet) northwest of camp, which we named “Trafton’s Gap”, and then on to the base of a dome like mountain where we cached our skis, put on our climbing boots, and began climbing the relatively easy southeast ridge to the summit. After all the anticipation it was good to finally be climbing! The ridge was nearly all hard wind-packed snow with patches of ice which made for good climbing. It wasn’t long before we reached the summit. This modest peak (6680’ 80 7.5N, 76 52W) we named Mount Kellet, after Sir Henry Kellet and British commander sent out on two of the British Admiralty’s expeditions (1848-50 and 1852-54) in search of Sir John Franklin. This, our first summit, gave us an expansive view of the Mer de Glas and the mountains around us. We built a rock cairn, about four feet tall, on the summit and put a note under the top rock to record and claim our first ascent.

Approaching Trafton’s Gap

Austin Peak from Trafton’s Gap

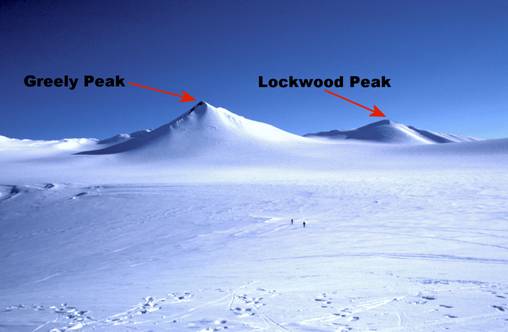

Looking toward Greely and Lockwood Peaks from Trafton’s Gap

After a few more minutes on the summit, enjoying the bright, warm sun we retraced our steps back down the ridge to our skis.

Don, Marty and Bill decided to return to camp while Al, Brad, Dave and I continued on, traversing about a mile due south to our second objective. After reaching the base of the mountain we split up. Al and I climbed the west ridge while Brad and Dave circled around and climbed the East Ridge. We all summitted within minutes of each other and celebrated on the 7300 foot summit (80 6.5N, 76 51W). This peak we named Mount Lockwood, after Lieutenant James Lockwood, a member of the Greely Expedition (The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition) of 1881-1884. Lockwood was a tireless hunter, writer, illustrator, and explorer of the northern coast of Greenland and Ellesmere Island. He discovered Greely Fiord which was to be to site of our final camp. Lockwood died with the rest of the Greely expedition and Cape Sabine, on the east coast of Ellesmere Island.

Al and I descended by the East Ridge completing our traverse of the peak. Brad and Dave descended with us. At the base of the mountain we put our cross country skis on and skied back to Camp 1. What a great start, two first ascents in one day, great skiing and a stable weather forecast for the next several days. We all were on a “climbing high.” The satisfaction of today’s accomplishments and the anticipation of tomorrow’s climbs made turning in for night an unwelcome diversion.

Summary of peaks climbed May 17, 1980.

(Map Below)

Trafton/Errington/Davis/Goodman/Waller/Adams/Albro. First ascent Mount Kellet/Peak 6680’

Trafton/Errington/Albro/Adams. First ascent via the east and west ridges meeting at the top. Mount Lockwood/Peak 7300’

Summary map of climbs May 17, 1980

May 18, 1980. After a restless night I got up at 7:00 a.m. for the morning “sked,” started breakfast and rousted the late sleepers out of the sack.

After breakfast we decided on a plan of operations for the day. We would field three different teams and target three peaks for ascent. Al and I would climb Peak 7600’ (later named Mount Greely) northeast of Mount Lockwood. Brad and Dave would climb Peak 7180’ (later named Mount Austin), about a mile southwest of camp and Don, Marty and Bill would take on Peak 6450’ (later named Mount Inglefield), about two miles west of camp.

Al and I left camp at 10:30, followed our ski tracks from yesterday, and reached Trafton’s Gap about an hour later. To the right was the south ridge of Peak 6450’ and across the snow field, just below us about a mile and a half away, was our objective Peak 7600’, the highest peak in the area. By 11:30 we reached the base of the peak and cached our skis (circa 5800 feet) at the foot of the northwest ridge. The first section of the climb was directly up the ridgeline to about 6800 feet. We then left the ridge and made an ascending traverse of a steep pale blue ice face of about 50 degrees for about five hundred feet (7300 feet), before climbing the final three hundred feet on gentler hard packed snow. We reached the summit (80 7.0N, 76 46W) at 2:45 p.m. and named this 7600 foot peak Mount Greely after Major Adolphus Greely, the American leader of the 1881-1884 expedition to northern Ellesmere Island (Grinnell Land) and NW Greenland. This was an ambitious and productive expedition, adding significantly to the knowledge of these remote regions.

Unfortunately this expedition ended tragically with the loss of its members to starvation near Cape Sabine.

After basking in the moment on the summit for about fifteen minutes we began our descent of the west ridge, avoiding the down climb of the step ice face. Near the bottom of the west ridge we cut over to the base of the northwest ridge and retrieved our skis. From there we skied back to Trafton’s Gap arriving about 4:00 p.m. Since it was still fairly early in the day we took the opportunity to quickly make the second ascent of Peak 6450’ (80 8.5N, 76 45.0W), following in Don, Marty and Bill’s footsteps. We summited at about 5:30 p.m. and named this peak Mount Inglefield after Sir Edward Inglefield, Captain of the British ship Phoenix sent in search of Sir John Franklin during 1853-54. Inglefield explored Smith Sound as far north as the Kane Basin between Ellesmere Island and Greenland. Inglefield named Ellesmere Island and also accompanied Lady Franklin’s private steamer, Isabel, to the arctic in 1852. After our ascent of Mount Inglefield we skied back to camp and arrived just before the 7:00 p.m. sked.

After the sked the three teams reviewed their day of “peak harvesting”.

Team one, Trafton/Errington. First ascent of Mount Greely/Peak 7600’ and second ascent of Mount Inglefield/Peak 6450’.

Team two, Albro/Adams. First ascent via the northeast ridge of Mount Austin/Peak 7180’

Team three, Waller, Davis, and Goodman. First ascent of Mount Inglefield Peak/6450’ and second ascent of Mount Lockwood/Peak 7300’.

Lockwood Peak from the slopes of Greely Peak

Ascending Greely with Lockwood Peak in the background

Al on the summit of Greely Peak

Just starting our descent from the summit of Greely Peak

Greely and Lockwood Peaks from Inglefield Peak

After basking in the glory of the day we decided that we would spend one more day climbing out of this camp and move our camp northeast up the ice cap to a new location near the next set of peaks about four and a half miles distant. The physical effort of the last two days was beginning to add up and we opted for an early to bed at 8:30. Temperature was 18 degrees and we had over twenty miles visibility.

Summary map of climbs May 18, 1980

=

So he left his home for the hell-town Nome,

On Alaska’s ice-ribbed shores,

And he learned to curse and drink, and worse,

“til the rum dripped from his pores;

When the boys on a spree were drinking it free

In a Malamute saloon,

And Dan McGrew and his dangerous crew

Shot craps with a piebald coon;

While the kid on his stool banged away like a fool

At a jag-time melody,

And the barkeep vowed to the hardboiled crowd

That he’d cremate Sam McGee.

=

May 19, 1980. I got up for the radio Sked at 7:00 a.m. We had an overnight low temperature of 2 degrees, but because the sun was out twenty-four hours a day the heat built up in our tents to a very warm 44 degrees. The wind was from the south at 5 – 10 mph and we had clear skies. This promised to be another great day for climbing!

The plan for the day was that Al and I would try for the second ascent of Mount Austin (80 7.5N, 76 40W), the 7180 feet just west of our camp. Dave, Don and Bill would do the second ascents of: Mount Lockwood/Peak 7300’ and Mount Greely/Peak 7600’. Marty and Brad decided to stay in camp and take a rest day.

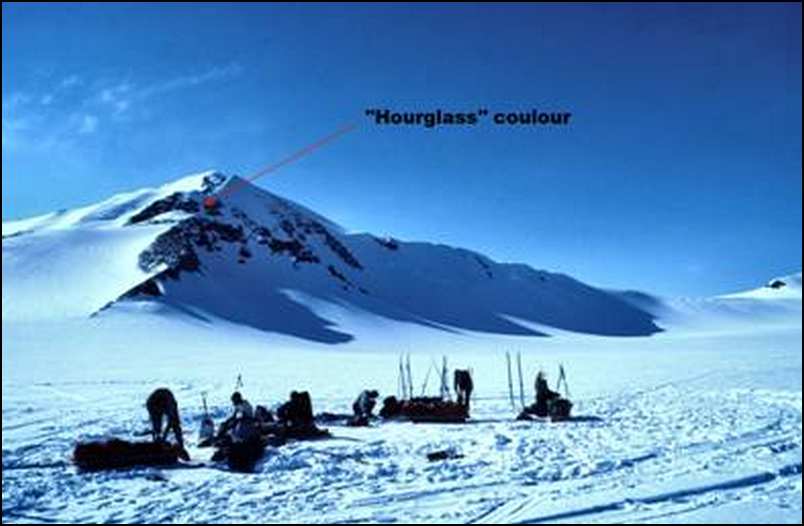

Austin Peak showing the “hourglass” on the north face

=

Since they would be in camp all day anyway Brad and Marty agreed to take long distance telephoto pictures of Al and me as we climbed Mt. Austin. We were going to do a variation on Brad and Dave’s route by climbing a steep hour-glass shaped coulour to gain the northeast ridge leading to the summit. Since the coulour was facing the camp it gave us a great opportunity for some third party shots from a little over a mile away.

=

Al and I left camp about 9:30 and started for the base of Mount Austin and an approach slope leading up to the “hourglass”. After climbing the easy approach slope we arrived at the coulour. After surveying the route and roping up Al led as we made our way up the coulour through knee deep snow covering 50 degree ice in the coulour. We belayed each other up about 200 feet to reach the northeast ridge. Once we had gained to the top of the coulour we followed a series of beautiful curving ridgelines and small snow fields to the summit. We arrived about 12:30 and spent a leisurely lunch break sunbathing on the summit and enjoying the fabulous view northeast along the axis of the Victoria and Albert Mountains. We named this peak Mount Austin after Captain Horatio Austin who led one of the first large scale searches for Franklin during 1850-51. He searched and explored much of the area around Cornwallis Island and Lancaster Sound. We descended via the northeast ridge and reached camp at 2:30. After one of the more picturesque ascents of the trip we spent the remainder of the afternoon lying around, drinking tea and reading “The Eye of the Needle”.

=

=

During 7:00 p.m. sked we heard the news that Mount St. Helens, in Washington State, had erupted. It was reported volcanic ash was blown 60,000 feet in the air and drifted as far away as Montana and Saskatchewan, Canada. Nine were confirmed dead and 27 were missing. This eruption had been anticipated for nearly six months, but the magnitude of the eruption was far greater than anyone had expected. The top 1500 feet of a mountain that we all had climbed many times was gone and now scattered over several states. This eruption was to prove to be one of the biggest volcanic events of the 1900’s.

=

A review of the peaks climbed May 19, 1980:

Team one, Trafton/Errington. Second ascent via the northeast ridge of Mount Austin/Peak 7180’

Team two, Adams/Goodman/Davis. Second ascent of Mount Lockwood/Peak 7300’ and Mount Greely/Peak 7600’.

=

Summary map of climbs May 19, 1980

=

May 20, 1980. 7:00 a.m., weather clear, 18 degrees, winds calms. After the sked and breakfast we began preparation for moving camp northeast four and a half miles. This would be our first big test of the new sled design and hopefully put us in a position to climb another series of peaks northeast of our current camp. Each of us loaded our individual sled with personal gear; clothing, sleeping bag and climbing boots, then we divided up the group equipment into seven shares and everyone added their one share to their loads. In addition to the load on the sled each team member also carried a back pack so the total load was nearly 225 pounds per person. Thus loaded we set out at 11:30 a.m. for Camp 2.

=

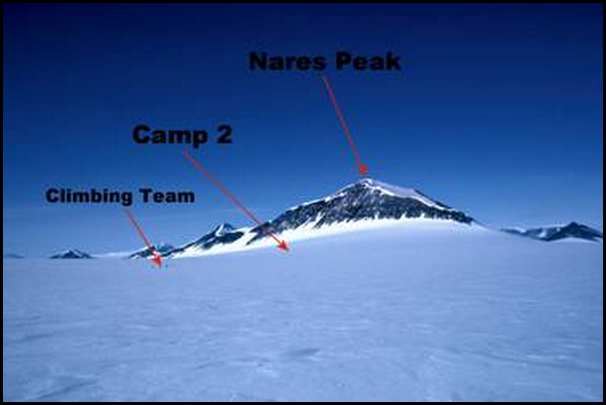

While the new sleds worked well, pulling a 175 pound sled while on skis carrying a 50 pound pack is hard work. Even though the glacier was smooth and fairly crevasse free we were still cautious and picked our route carefully, always on the alert for anything that suggested hidden crevasses. As for speed, sledding isn’t a speedy mode of travel. We made about 1 – 1.2 miles/hour on average. We also soon discovered that even the slightest uphill grade multiplied the effort several fold, so while on the flat we could maintain a 2.5 mph pace, any uphill sections slowed the pace to an agonizing 0.5 – 0.75 mph. The only consolation was the incredible scene we were pulling through and the residual sense of achievement we all felt after the first few days of climbing. After three hours struggling with the sleds we reached our new campsite. Camp 2 was pitched at 80 10.5N, 76.15W at 5500 feet.

=

-

- The author starting out from Camp 1 en route to Camp 2 with fully loaded sled with Austin Peak in the background

=

During the 7:00 p.m. sked we gave the PCSP base at Resolute Bay the coordinates of Camp 2 and spent a little time giving information on the Victoria and Alberts to a geologist stationed at Cape Herschel. That evening the temperature was 14 degrees, the winds were calm and the visibility was 30+ miles. Another balmy evening in the arctic!

=

Route between Camp 1 and Camp 2, May 20, 1980

=

Then Jacob Kaime, who had taken the name

Of Yukon Jake the Killer,

Would rake the dive with his forty-five

‘Til the atmosphere grew chiller;

With a sharp command he’d make ‘em stand

And deliver their hard earned dust;

Then drink the bar dry of rum and rye,

As a Klondike bully must;

Without coming to blows he would tweak the nose

Of Dangerous Dan McGrew,

And, becoming bolder, throw over his shoulder

The lady that’s known as Lou.

=

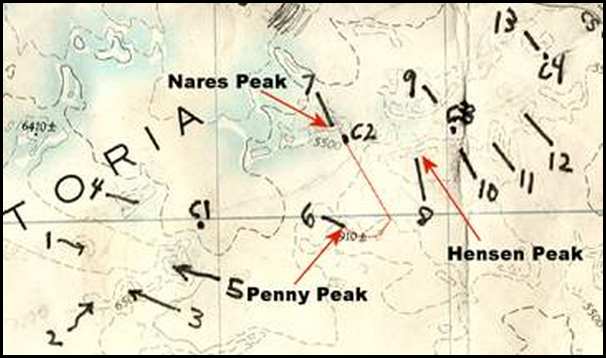

May 21, 1980. All hands were up by 7:00 a.m. and ready to go summit hunting once again. Al and I set out for Peak 7000’ (latter named Mount Penny), about two miles south of Camp 2 and three and half miles due east of our first camp. Dave, Brad and Don went after Peak 6800’ (latter named Mount Hensen), about a mile east of camp. Bill and Marty choose Peak 6500’ (latter named Mount Nares), about a quarter mile northwest of camp.

=

We all left camp around 9:00 a.m. Al and I skied across the glacier to the base of the step face leading to the southeast ridge of the mountain. We ascended the thousand foot shallow face on intermittent blue ice and hard snow to reach the southeast ridge. Once above the face we then followed the beautiful gently ascending sharp ridge to the summit (80 8.0N, 76 17.0W). We named this peak Mount Penny after Captain William Penny the commander of the 1850-51 Franklin search expedition aboard the ships Lady Franklin and Sophia. Once again we took our time and enjoyed the summit, having lunch, taking pictures and relaxing in the sun.

=

While lounging about the summit enjoying the moment I wondered if the intensity and breadth of the emotional as well the physical aspects of our expedition would endure crisp and clear in my mind or fade over time until only a vague recollection remained. I found myself focusing on the experience, trying to indelibly sear it into my memory and hoping that, some years from now, I would be able to recall not only the enormity and beauty of the scenery but also the flood of intangible mental sensations encompassing my response to the remoteness of our position, the euphoria of being the first to ascend these mountains and the charge of apprehension regarding what new challenges would be revealed in the coming days.

=

=

We left the summit of Mount Penny/Peak 7000’ and retraced our route back to Camp 2 arriving at 2:30 p.m. After some tea and a light snack we lazed the rest of afternoon away and compared climbing notes and experiences with the other teams. Don, Dave and Brad reported a successful ascent of the west ridge of Mount Hensen/Peak 6800”. This peak was named after Mathew Hensen, Robert Peary’s loyal and indispensable companion on all of his polar trips after 1887. He was a rare non-Eskimo master of dog sledding and Eskimo style hunting. He accompanied Peary and four Eskimos to the North Pole in 1909. Bill and Marty were likewise successful in climbing the east ridge of Mount Nares/Peak 6500’. Mount Nares was named after Admiral Sir George Nares, commander of the Challenger during the Franklin search of 1872-74. He returned to the arctic in 1875 as commander of the Alert and the Discovery and successfully explored as far north as Cape Columbia (about 83N), the northern tip of Ellesmere Island.

=

A review of the peaks climbed May 21, 1980:

Team one, Trafton/Errington. First ascent of Mount Penny/Peak 7000’

Team two, Adams/Goodman/Albro. First ascent of Mount Hensen/Peak 6800’

Team three, Waller/Davis. First ascent of Mount Nares/Peak 6500’

=

Summary map of Penny Peak First Ascent May 21, 1980

=

May 22, 1980. I overslept a little this morning and missed the 7:00 a.m. sked by two minutes. Another beautiful day in the arctic; 6 degrees, calm winds and visibility 20+ miles. We decided to make a group climb of Peak 6850’ which lay east northeast of Camp 2 about a miles distant.

We set out on skis after breakfast and traversed to a col near the base of the mountain and started up a four hundred foot avalanche slope. This slope brought back memories of the avalanche we experienced in 1978 on Baffin Island and it was with some relief that we reached the top of the slope and gained the beautiful icy west ridge that led to the summit (80 12.5N, 76 2.5W). We named this peak Mount Pullen after Captain William Pullen of the HMS North Star during the Franklin search of 1852-54. Pullen established Beechey Island as a major supply depot for other Franklin search expeditions. Earlier in his career, as a lieutenant he commanded five small boats for the Herald, Plover and Nancy on a boat voyage from Bering Strait to the Mackenzie River in an effort to locate Franklin from the western portal of the Northwest Passage.

=

Near the summit of Pullen Peak

=

After a great country ski run on the return from Mount Pullen we rested for a while and ate dinner. Since it was still early we decided to make an after dinner second ascent of Mount Nares/Peak 6500’. This peak fell for the second time in record time, about one hour fifteen minutes for the round trip! It was obvious that after a few days of climbing and skiing we were getting to be in pretty good shape and able to be more aggressive in our ascents. After our return to camp we had tea, wrote in our diaries and read until “lights out” at about ten.

=

Nares Peak rises dramatically behind Camp 2

=

A review of the peaks climbed May 22, 9180.

=

Trafton/Errington/Albro/Waller/Goodman/Adams/Davis. First ascent of Mount Pullen/Peak 6850’ via the west ridge. Second ascent of Mount Nares/Peak 6500’ via the East Ridge.

=

Oh, tough as a steak was Yukon Jake,

Hardboiled as a picnic egg;

He washed his shirt in Klondike dirt,

And drank his rum by the keg.

In fear of their lives, or because of their wives,

He was shunned by the lest of his pals;

And outcast he, from the camaraderie

Of all but wild animals.

So he bought him the whole of Sharktooth Shoal,

A reef in the Bering Sea,

Where he lived by himself on a sea-lion’s shelf

In lonely iniquity.

=

May 23, 1980. A heatwave has struck! Its 73 degrees inside the tents and the outside temperature has risen to 13 degrees. It’s sunny and clear, the winds are calm and the visibility is 20+ miles.

After breakfast Al and I headed for Mount Hensen/Peak 6800’ for a second ascent, while Bill, Dave and Don left shortly after us to repeat our climb of Mount Penny/Peak 7000’. Marty and Brad decided to load two sleds and make a pull to our next campsite further up the valley. This significantly lightened loads for everyone when we would move from Camp 2 to Camp 3 tomorrow.

Al and I left camp about ten and headed out across the glacier toward Mount Hensen. It was a clear sunny day and the snow conditions were perfect for skiing. We cached our skis at the base of the slope leading to the west ridge and ascended about five hundred feet up the slope to a grand sweeping west ridge. Here we followed an alternating rock and snow covered ridgeline to the steep summit slope. The last three hundred were 50 degree hard blue water ice which we climbed reaching the summit at 12:45 p.m. We were able to see Marty and Brad slowly traversing their way across to the col northeast of Camp 2 pulling their loads on to Camp 3. We could also make our camp 1300 feet below us on the glacier.

=

-

- Al and I beginning our descent from the summit of Hensen Peak. The picture was taken from Camp 2 with a 600mm telephoto lens

=

After a short rest on the summit we began our descent. Just below the summit slope we stopped at a rocky point, high on the west ridge, and took about an hour out to build a large rock Inukshuk (rock cairn shaped to resemble a man standing with his arms outstretched). We left a note in the top rocks, declaring this land and all that could be seen from this site under the sovereignty of the State of Washington. To this day we haven’t heard from anyone challenging this claim of sovereignty and so our “stone man” still rules over the Victoria and Albert Mountains at 80 degree north.

=

Our Inukshuk on the west ridge of Hensen Peak

=

Turning our backs to the stone man we continued down the ridge and then down the approach slope to our skis. After changing out of our climbing boots and into our ski boots we enjoyed a sunny and leisurely ski tour back to camp. Marty and Brad returned about an hour after us and reported that they had found a good site for Camp 3 about three miles up the glacier. They left two loads of group equipment cached there, thus greatly reducing the weight the rest of us would have to carry the following day. They also reported that the pull to Camp 3 wouldn’t be easy since we had to pull the sleds over a short, but relatively steep section of the glacier between the two camps. All our sled experience had taught us that pulling a sled on level terrain was not easy, but do-able. However pulling a loaded sled uphill, even at a gentle angle multiplied the work effort several fold. They both assured us that we would earn our keep the next day.

During the 7:00 p.m. sked we asked Frank Hunt, PCSP Camp Manager, to check in Bradley Air Service about our proposed landing site in Greely Fiord. We had been somewhat unclear as to whether we would be able to get to Greely Fiord from our position on the Mer de Glas Agassiz but as we gained experience with these mountains we now felt confident that we could. However, we also advised Frank that the final decision as to the landing site would have to wait until closer to the pick up date depending on our progress. Frank said that he would relay our message to Bradley and that he was sure that whatever we decided would be okay with them.

=

A review of the peaks climbed May 23, 1980.

=

Team one. Trafton/Errington. Second ascent of Mount Hensen/Peak6800’ via the west ridge.

Team two. Adams/Goodman/Davis. Second ascent of Mount Penny/Peak 7000’ via the southeast ridge.

Trafton/Errington/Adams/Goodman/Albro. Second ascent of Mount Nares/Peak 6500’ via the East Ridge.

=

=

May 24, 1980. After the 7:00 a.m. radio check-in we dismantled Camp 2, loaded our sleds, and began the push to Camp 3. After a gentle start we started the uphill portion of the route. This section of the route was too steep to be attacked head-on so we made several long traverses of the slope gradually gaining altitude until reaching the col at 6000’. I was certain that this hour long section of the trip required more energy than three or four hours of level sledding. We reached the col at 12:30 p.m. and took a break for a quick lunch and then started the gentle descent to Camp 3 (80 11.5N, 76.0W) at 5800 feet.

=

Arriving at the col between Camp 2 and Camp 3 with Hensen, Austin and Nares in the background

=

Route from Camp 2 near Nares Peak to Camp 3 below Isachsen Peak

=

This camp was located in a shallow basin across from Mount Pullen and with virgin peaks lined up south and east of our camp. We hoped that these three silent sentinels were about to fall prey to our enthusiastic onslaught.

=

Camp 3 with Sverdrup Peak in the background

=

A little later in the afternoon some high strato-sirus clouds began forming and a light wind from the west began to rustle the tents. It looked as though the weather was about to change. The good news is that generally arctic weather this time of year is slow to change and it might take another day or to before any storm developed. During the 7:00 p.m. sked Bradley Air Service passed on a message that they would be able to pick us up in Greely Fiord. We agreed to notify them when we arrived at the fiord in another ten or eleven days. We also got the update on Mt. St. Helens. The death toll had risen to 39 and 71 people were still missing.

=

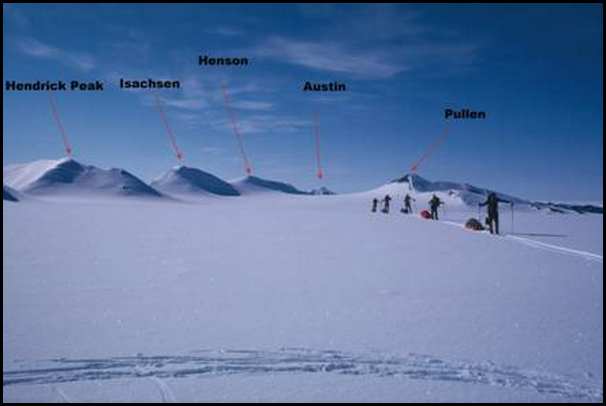

May 25, 1980. The weather this morning was about 60% overcast with high strato-sirus, temperature 20 and the winds were calm. It wasn’t as sunny as we were used to by now but still good climbing weather. Instead of breaking into three groups we decided to climb as one larger group of five. Brad, Al, Dave, Don and I would climb as two rope teams and try to do the three peaks around the camp the camp in one day.

=

We left camp at 9:30 a.m. and started for the col between Peak 7000’ (later named Mount Isachsen) and Peak 6850’ (latter named Mount Hendrick) After reaching the col we started up the east ridge of Peak 7000’. We encountered hard blue water ice, perfect for climbing and a few small crevasses but nothing too serious. We were on the summit (80 11.0N, 76 W) by 12:00 noon and back at the col by 1:00 p.m.

=

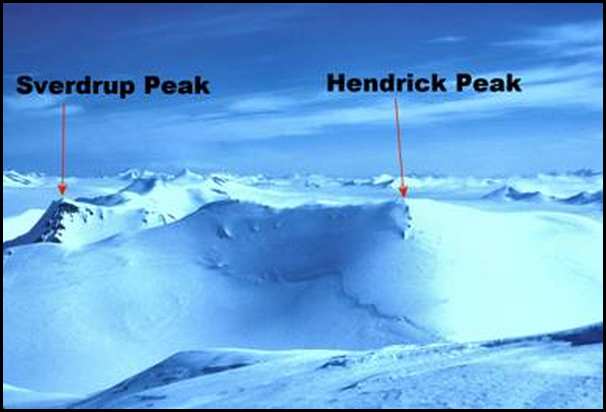

On the summit of Isachsen looking toward Hendrick and Sverdrup Peaks

=

We named this peak Mount Isachsen after the Norwegian explorer who, with Otto Sverdrup, traversed northern Ellesmere Island, discovered Axel Heiberg Island and the Ringnes Islands during 1898-1902. We then started up the southwest ridge of Peak 6850”. Just above the col we found 60-65 degree blue ice for about 300 feet. This gave us a nice, but not too heroic, bit of technical climbing before the easier summit slopes. We reached the summit (80 10.5N, 75 55.0W). This peak was named Mount Hendrick, after the Inuit Hans Hendrick who played a vital role in the many northern expeditions. He was employed by Elisha Kent Kane as a hunter and was central to Kane’s successes. During a period of 25 years he and his wife Markut rendered help to Hayes, Hall and Nares. After a careful descent of steep ridge we reached the col at 2:15 p.m. and switched from climbing boots to skis for the traverse around Peak 6850’ to the base of Peak 6800’. After shedding our skis once again we started climbing the approach slope to the beautiful knife edged southwest ridge. Along the way we skirted a number of large cornices that guarded the ridge crest and eventually reached the summit (80 11.0N, 75 52.0W) at 4:00 p.m.

=

Cornice protecting the southwest ridge of Sverdrup Peak

=

Approaching the summit on Sverdrup

=

This peak we named Mount Sverdrup after Otto Sverdrup, captain of the Fram during a successful expedition to Ellesmere Island during 1898-1902. He and Isachsen accounted for major explorations of northern Ellesmere Island, Axel Heiberg Island and the Ringnes Islands. He was the leader of an expedition in 1914-15 in the search for the lost Russian explorer, Brusilov. After descending back to our skis it was only about a half hour ski tour back to Camp 3. We arrived back at 5:30 p.m. and checked in with Marty and Bill who had opted to stay in camp and do some ski touring. It had been a long, but successful day.

=

A review of the peaks climbed May 25, 1980.

Trafton/Errington/Albro/Adams/Goodman. First ascent of Mount Isachsen/Peak 7000’ via the East Ridge. First ascent of Mount Hendrick/Peak 6850’ via the southwest ridge. First ascent Mount Sverdrup/Peak 6800’ via the west ridge.

=

Summary map of peaks climbed May 25, 1980

We planned to move camp the next day further up the glacier to yet another set of mountains. The weather that night was cloudy, 0 degrees with calm winds.

=

But miles away, in Keokuk,

Did a lovely maiden fight

To remove the smirch from the Baptist Church

By bringing the heathen light;

And the elders declared that all would be squared

If she carried the Holy Words

From her Keokuk home to the hell-hole Nome

And save those awful birds.

So two weeks later she took a freighter

For the gold-cursed land near the Pole,

But heaven ain’t made for a girl that’s betrayed,

She was wrecked on Sharktooth Shoal!

=

May 26, 1980. 7:00 a.m. weather, foggy, windy, cold, blowing snow. Into every arctic expedition a little cold wind must blow. The little storm that had been developing over the past few days arrived at last. While the conditions weren’t too bad they were bad enough that travel would have been counterproductive in the fog and blowing snow so we decided to wait out the storm in the tents and take a day of rest. Out first since the expedition began. Almost every expedition has idle days due to weather or the need for rest. In this case both probably applied. The usually soundless surroundings we had grown used to gave way to a veritable Arctic symphony. The wind blown snow had a sound similar to that of the metal brush like drum sticks on the skin of a snare drum. This soft raspy sound was punctuated by the more percussive flapping of the tents in the wind. The variations in wind strength provided the melody for day leisurely reading and periodic napping. Al and I spent a good portion of the day reading Tom Robbins’ Another Roadside Attraction. Because we had only one copy I would read 20 – 30 pages and then tear them off and pass them along for Al to read. When we tired of reading we would take a break and brew some tea or soup and talk amongst the tents reliving climbing stories. I even gave a reading of “The Cremation of Sam McGee” to the captive audience. Occasionally we would venture outside to check the weather and shovel the accumulated snow away from the tents and equipment. While not the most exciting part of the trip it was a nice interlude and chance to just relax and enjoy the arctic solitude.

=

Weather starting to close in around Camp 4

=

Camp 4 during light storm

=

May 27, 1980. We were up at 7:00 a.m. for the sked. The weather, clear skies, 18 degrees, calm winds and visibility 20+. The storm was indeed a short one and was a great day for moving camp. After breakfast we loaded the sleds, got back into the harnesses and began the pull to Camp 4 (80 12.0N, 75 50.0W). The pull as pretty easy compared to the one between Camp 2 and Camp 3. We made good time, across the relatively flat glacier and reached the site of Camp 4 by shortly after noon. We established Camp 4, had some lunch and sited our first objective. Peak 6800’ (later named DeHaven Peak).

Pulling to Camp 4

=

Route to Camp 4 May 26, 1980

=

We left camp about 1:00 p.m. Al, Brad, Dave, Don and I climbed via the south buttress. The buttress was about 800’ of class three rock which was a nice change from the usual snow and ice ridges we had been faced with on most of the climbs. After surmounting the buttress an intricate series of crevasses guarded the summit and we had to slowly pick our way through this maze to gain the last easy summit slope. Martin and Bill paralleled our route and climbed via the south ridge meeting us just below the summit (80 12.5N, 75 47.0W). After summiting we built a rock cairn to celebrate our victory over De Haven/Peak 6800’ (We also referred to this peak as Community Peak in honor of our group climb.) We named this peak after Lieutenant E. J. De Haven, commander of the U.S. ships Advance and Rescue sent by Henry Grinnell to search for Franklin in 1850-51. De Haven searched Lancaster Sound and Wellington Channel. We spent nearly two hours on top throwing rocks off and the enjoying the view. The wind began to come up a little while we were on the summit but all in all it was another great day in the arctic.

=

=

All hands were tossed in the sea and lost,

All but the maiden Ruth,

Who swam to the edge of the sea-lion’s ledge

Where abode the love of her youth.

He was hunting a seal for his evening meal

(He handled a mean harpoon)

When he saw at his feet not something to eat,

But a girl in a frozen swoon;

He dragged her to his lair by the frozen hair,

And he rubbed her knees with gin

To his great surprise she opened her eyes,

And revealed-his original sin!

=

May 28, 1980. 7:00 a.m. sked weather reported to PCSP, Resolute Bay; 80% cloud cover, visibility 10+ miles, winds 5 – 10 mph. We asked Frank Hunt about possibly sharing a plane with another group for our flight out from Greely Fiord about June 7th– 11th. Chartering a Twin Otter in the arctic was expensive even with the government discount we were getting so we hoped that perhaps another group would be scheduled to fly into the Eureka/Greely Fiord area during those dates and that we might be able cut our expense down to only the one way cost of returning to Resolute Bay. Frank said he would keep it in mind when scheduling the flights and let us know as the time for pick up became more certain.

We noted that this morning we had begun to “gain” altitude, as measured by our altimeters. Since we were obviously at the same actual altitude as we were the night before it meant that the barometric pressure was falling giving a false reading to the altimeters. It also meant that the weather was likely to deteriorate during the next twenty four hours. With this in mind and since we had climbed all the relevant peaks near this camp we decided to move to Camp 5 as soon as possible so that we would be in position to climb that next group of mountains as soon as the weather improved.

=

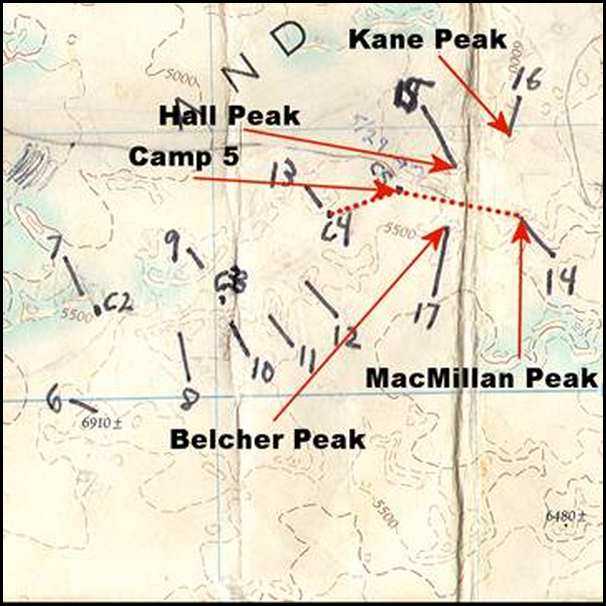

We loaded the sleds and our backpacks and began the two to three mile pull to our next camp. During this trek the wind continued to build and by the time we reached Camp 5 it was blowing 15 -20 mph. The visibility was still pretty good at about 10 miles so after establishing Camp 5 (80 13.5N, 75 38.0W) at 5700’. Al and I decided to attempt one more climb before the weather closed in. We left camp in the early afternoon and struck out for Peak 7150’ (later named Mount MacMillan), about five miles east-southeast of our camp.

=

After about an hour of skiing across the glacier we reached a point, at the base of the mountain, where we cached our skis and donned climbing boots for the ascent. We picked the southwest ridge as our route and started up the approach slope. After gaining the ridge in gusting wind conditions we carefully traversed our way along its crest to a beautiful blue ice dome that protected the actual summit. After putting on our crampons we traversed this wind swept dome and at last stood on the summit (80 12.0N, 75 22.5W). We named this peak Mount MacMillan after the American, Donald MacMillan, who led the MacMillan Crocker Land Expedition of 1913-17. He explored the area northwest of Ellesmere Island, but was unable to confirm the existence of Crocker Land reported by Peary in 1906.

=

MacMillan Peak from Camp 5

=

It was quite windy on the summit, so as beautiful as this position was Al and I quickly congratulated each other and headed down the ridge. On the way down we met Don and Dave just below the ice dome. We wished them well continued on down the ridge to our cache of skis and then on back to camp. For such a marginal day we had accomplished a lot. That evening the wind continued to pick up from the ENE and the cloud cover built. Later it started to snow lightly; the temperature at 7:00 p.m. was 6 degrees, wind 10-15 mph and the visibility 5 miles. About 11:00 p.m. the weather began to moderate and we thought that perhaps tomorrow might be climbable weather.

=

Review of the peaks climbed May 28, 1980:

Team one. Trafton/Errington. First ascent of Mount MacMillan/Peak 7150’ via the southwest ridge.

Team two. Goodman/Adams. Second ascent of Mount MacMillan/Peak 7150’ via the southwest ridge.

=

Dave and Don on the summit ridge of MacMillan Peak

=

Move to Camp 5 and climb of Macmillan Peak May 28, 1980

=

May 29, 1980. We awoke to clear weather and light winds with 20+miles of visibility. Because of the break in weather and the need to start for Greely Fiord in the next few days we decided to put forth an all-out effort to finish the climbing in the “Explorer” group of the Victoria and Alberts.

Don, Marty and Dave left to climb Peak 6750’ (latter named Belcher Peak), about three miles southeast of camp.

=

Al and I left camp at 9:30 a.m. and skied three miles east to Peak 7000’ (later named Mount Hall). This peak rose out of the glacier as an almost perfect cone very reminiscent of Mount St. Helens or a miniature Mount Fuji. We reached the base of the southwest ridge, cached our skis and ascended this snow and ice ridge to the summit (80 14.0N, 75 34W). We named this peak Mount Hall, after Charles Francis Hall, an American explorer who traveled along the northern Ellesmere and Greenland coasts on board the U.S. navy ship Polaris, in 1871. He was prominent in the Franklin search expeditions of 1860-62 and 1864-69. Hall is generally considered to be one of America’s greatest explorers. He died under mysterious circumstances aboard the Polaris on his last expedition. It was later discovered that Hall had died after having been poisoned by the ship’s doctor.

=

First Ascent Route on Hall Peak May 29, 1980

=

Don and Dave descending Hall Peak: Photo taken from Camp 5

=

After our ascent of Mount Hall we descended and skied on to Peak 6800’ (Later named Mount Kane). We ascended its gentle southwest ridge on mixed snow and ice to the summit (80 14.5N, 75 27.0W). We named this peak Mount Kane after Elisha Kent Kane the American explorer, surgeon and writer who explored north to Smith Sound, the Kane Basin, Greenland’s Humboldt Glacier and Grinnell Land (Ellesmere Island) during the American financed Franklin searches of 1850-51 and 1853-55.

=

On the return from Kane Peak

=

We completed this fabulous last day of climbing with the second ascent of Peak 6750’ (later named Mount Belcher). This we climbed via a very icy, but only moderately steep south ridge to the summit (80 12.0N 75 35.0W). We named this last peak on our grand tour Mount Belcher after Lieutenant Frederik Mecham who explored much of the area west of Melville Island during the 1852-54 expedition led by Leopold McClintock.

=

Belcher Peak from Camp 5

=

Midway up the West ridge of Belcher Peak

=

With the climbing portion of the expedition now complete we began to contemplate our route some 40 – 45 miles down the d’ Iberville Glacier to Greely Fiord. The route looked pretty straight-forward but we had no way of knowing with certainty whether this route was possible since no one had ever done it before. We were counting on the possibility that if the route wouldn’t work that we could have the plane land on the glacier to pick us up. With this thought in mind we spent our last night on the Mer De Glas Agassiz. 7:00 p.m. weather; clear, 14 degrees, visibility 20+ miles and calm winds.

=

Review of the peaks climbed May 29, 1980:

Trafton/Errington. First ascent of Mount Hall/Peak 7000’ via the southwest ridge. First ascent of Mount Kane/Peak 6000’ via the south ridge. Second ascent of Mount Belcher/Peak 6750’ via the west ridge.

Adams/Goodman/Waller. First ascent of Mount Belcher/Peak 6750’ via the west ridge.

Albro/Davis. Second ascent of Mount Hall/Peak 7000’ via the southwest ridge.

=

Summary map of peaks climbed May 29, 1980

=

His eight months’ beard grew still and weird,

And it felt like a chestnut burr;

He swore by his gizzard and the Arctic blizzard,

That he’d do right by her.

The cold sweat froze on the end of his nose,

‘Til it gleamed like a Teckla pearl,

While her bright hair fell like a flame from hell

Down the back of the grateful girl.

=

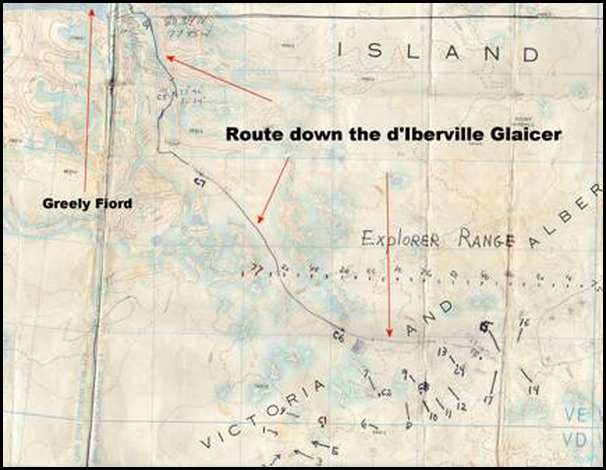

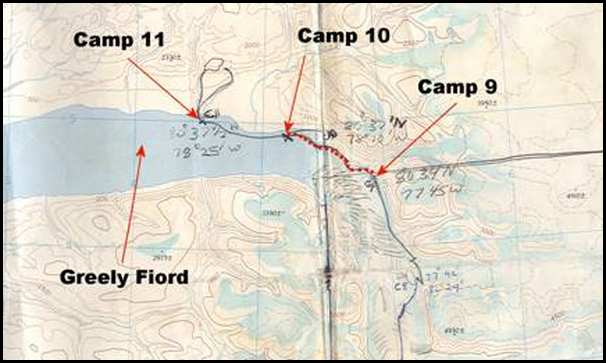

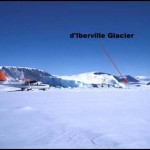

May 30, 1980. 7:00 a.m. weather; clear, winds calm, temperature 12 degrees and the visibility 20+ miles. After a successful traverse across the Victoria and Albert Mountains we were about to enter a new phase of our expedition. We planned to descend from the Mer de Glas Agassiz plateau via the d’Iberville Glacier to d’Iberville Inlet off Greely Fiord. This route was about 45 miles of glacier travel along a route never before undertaken. We knew from past experience that a glacial route that looks straight forward on a large scale map might in fact turn out to be jumble of ice falls and crevasses. This route could go in two days or might not be possible in thirty. The only way to find out was to commit and hope for the best. We certainly didn’t look forward to re-ascending back up the route again to the plateau where the only good landing sites would be.

=

Route from Camp 5 to Greely Fiord via the d’Iberville Glacier

=

We started out about 10:30 a.m. just as a fog bank came rolling up the d’Iberville Glacier valley surrounding us and reducing visibility to about 100 yards. Thus blinded by the fog we pressed on, navigating by map, sun position and altimeter.

=

Navigating in the fog: Only 45 miles to go!

=

Emerging from the fog below Camp 5 while descending the d’Iberville Glacier

=

We initially thought that the trip from Camp 5 down the glacier would be an easy downhill glide on our skis, but it soon proved to be any thing but. Ordinarily, traveling downhill on cross country skis is easy enough and makes for an enjoyable way to spend the day, but with one hundred-ten pounds of sled and a backpack on it becomes a major challenge. The sled is either pushing or pulling the skier unexpectedly while his forty plus pound backpack makes him top heavy and multiplies the impact of the lurching caused by the sled.

=

In addition to the pushing and pulling action each time the skier turns, his backpack exaggerates the centrifugal force of the turn. And then the sled, once started into a turn, skids to the outside of the turn further pulling the skier off-balance. After a few minutes of this off-balance ballet, in an effort to escape the almost impossible mission of controlling the direction of the sled and coordinating the independence of the sled and the backpack, the skier tries the extended straight downhill technique. While this relieves the turning control problem it definitely raises a serious new issue. STOPPING! Stopping the top heavy tractor-trailer type vehicle that the sled puller has now become requires a combination of determination and skill, augmented with a lot of luck. Most of the time straight-line descenders simply execute a series of semi-controlled crashes to check their speed.

=

Each crash also elicited a hearty expletive to punctuate the event. This picture was multiplied by seven as each member of the expedition continued his descent. In addition, the crashes needed to be anticipated because the total stopping distance required varied from one hundred to three hundred feet, depending on the skill level, strength and eminent danger level in not stopping. Since the foggy conditions limited visibility to about one hundred yards our stopping distance equaled our sight distance which meant we were always on the cusp of not being able to stop in time by the time we saw some impasse before us.

=

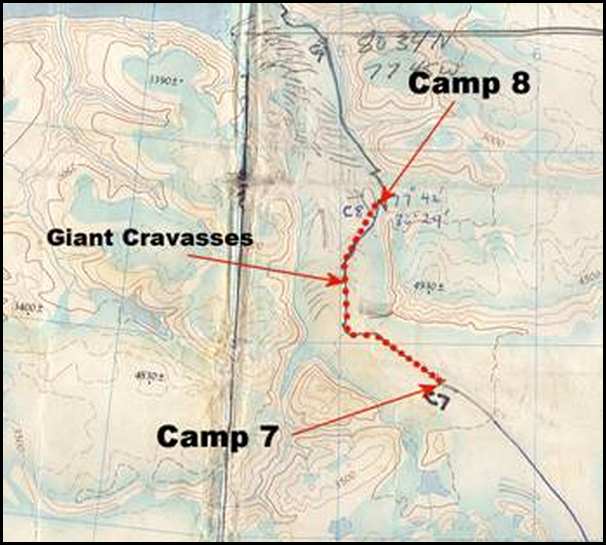

After about six miles, at 5000’ we broke out of the fog. At least now we could see the terrain we were venturing into. Our relief at being able to see the route before us was short lived when we discovered that we were in the midst of massive hidden crevasse field. These large crevasses were rendered invisible by a wind blown snow cover, about one to two feet thick, which blended perfectly with the surrounding solid part of the glacier. These hidden crevasses were a very dangerous and perhaps fatal obstacle which had to be navigated very carefully…lest one or more of the team broke through the crust and plunged a hundred feet to the bottom. Even if the unlucky one who broke through were held by the climbing rope between sleds, extricating both man and sled from the crevasse would have been very difficult.

=

Once we had determined that everyone was on solid ice we roped up so that the second person on the rope was roped to the leader’s sled and then to the leader. We did this so that if the leader broke through, the rope would first support the sled and then the climber. This way the leader wouldn’t be dangling inside the crevasse with his sled hanging unsupported from his waist. This would have made it difficult, if not impossible to rescue him from the crevasse. Even with this precaution, if some one broke through we would have to first lower a second rope to him with which we could secure him independent of the sled. He could then disconnect from the sled and be brought to the surface, after which we could retrieve his sled using the original rope. Of course the thinness of the crevasse covering further complicated potential rescue activity because the rope would cut into the opening of the crevasse so that anything or anyone that was being brought to the surface would first have to cut a new hole in the roof of the crevasse to escape. All these complications basically meant that falling into one of these behemoths would be, at best, most unpleasant for everyone.

=

In order to navigate this maze of well hidden crevasses we began the process of probing each step of the way with our ski poles and following precisely in the path of the ones who had gone first. Even then occasionally the second, third or fourth person might break through in a place that was previously probed and thought to be safe. Another very eerie and disconcerting nuance to this already riveting experience was that if you were over a crevasse, even if you didn’t break through with the probe, pieces of ice would be broken off from the bottom side of the crust and fall deeper into the crevasse. This ice fall was clearly audible on the surface and created a heart stopping few seconds when we were certain that the crust beneath us was about to give way. We didn’t even want to think of the circumstance where the leader probed and, thinking it was safe, continued on while the second or third sled finally broke through taking everyone on that rope down with him. In that case there would be, at the least serious injuries and most likely no rescue possible.

=

Probing the route for hidden crevasses

=

Fortunately this first encounter with crevassing lasted only about an hour before we reached safer traveling. This lasted for about four miles, until we reached an intersection with another arm of the glacier. The two intersecting glaciers created another crevasse field, much larger than the first one. Our worst case scenario came very close to occurring while crossing this crevasse field when, as four of us were on an apparent ice bridge over a huge crevasse, Brad broke through. We were all directly over at least a hundred feet of hidden crevasse. It was very tense for about 20 minutes as we all tried our best to walk on air and hoped the bridge would hold until we reached solid ice.

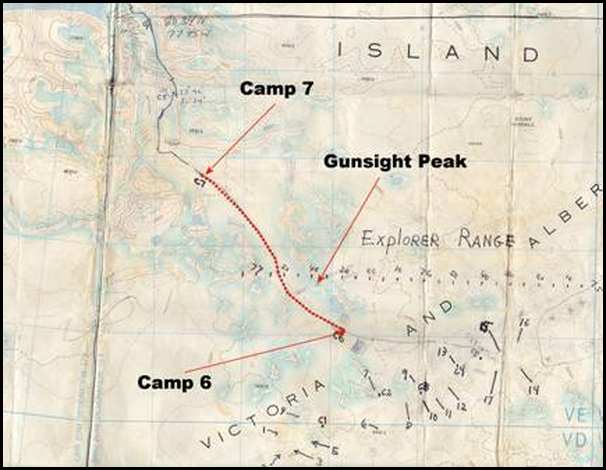

After several more hours of nervous probing we reached the other side of the crevasse field just as it started to snow. We set up Camp 6 (80 16N, 76 40W) at 4150 feet elevation, still 30.5 miles from Greely Fiord.

=

Camp 6 with “Gunsight Peak” in the background

=

Route from Camp 5 to Camp 6: May 30, 1980

May 31, 1980. 7: a.m. weather; overcast, 22 degree, calm winds and visibility 10+ miles. After yesterday’s ordeal we decided to sleep in a bit longer than usual and so it was 10:30 by the time we had made breakfast, packed and were on our way. This day our work was eased considerably by the steeper gradient of the glacier and the lack of crevasses. We pulled for about 6 hours and made 16.5 miles before reaching Camp 7 (80 25N, 77 40W) at 2150 elevation.

=

Route from Camp 6 to Camp 7: May 31, 1980

=