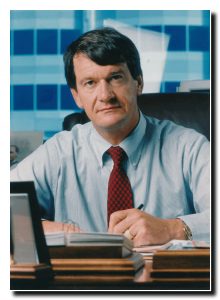

Steve Trafton’s book entitled At The Edge, is now published and available at Amazon. You will find short excerpts of the writing below. Additional photos for some of the chapters are also shown in the links under the Book menu above.

For a pretty normal guy, Steve has done a lot. He has led more than 200 mountain rescues during his lifetime, survived an avalanche, climbed over 600 mountains, roamed through the remote Arctic where he has 32 first ascents, searched and found evidence of the 1845 Franklin Expedition. And oh yes, at the age of 64 he gained a World Speed Record at the Bonneville Salt Flats.

Of course he also trekked the width of the United States, scaled each state’s high point, hiked the Alps, attempted the 8500 mile Peking to Paris Motor Challenge in a 1915 speedster, and as a corporate CEO gained the largest ever monetary judgement against the U.S. Government in a landmark opinion by the U.S. Supreme Court.

.

.

Then he authored a book on how you too can do similar things. Yes, it traces adventures in Steve’s achievement-oriented life, but also gives a road-map for the reader who wants to prompt similar events in his own life.

.

.

AT THE EDGE

A life in search of challenge in Arctic exploration,

mountain climbing, business and land speed record racing.

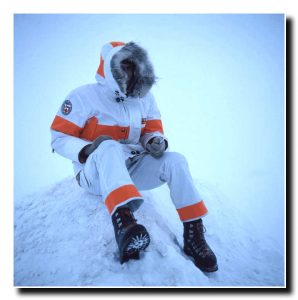

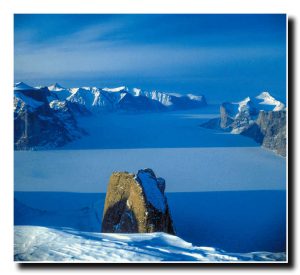

Baffin Island 1978

Ellesmere Island 1980

Mountain Rescue 1967 – 1980

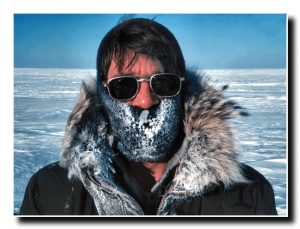

Arctic Short Stories 1979, 1981, 1982

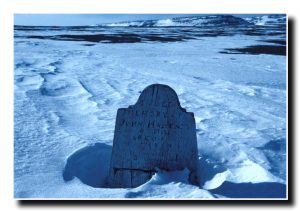

King William Island 1977

Return to King William Island 1989

Who Am I? 1946 – 1968

Banking at the Edge 1969 – 1998

The Need for Speed 2007 – 2010

Find Your Edge

New Horizons 1996 –

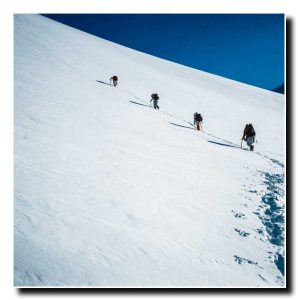

From Chapter 1: Baffin Island 1978

“This was a dumb ass idea.”

As Al recalls; “It wasn’t long after, that I told everyone to spread out, less than a minute, when 20´ above me I could hear ‘RRRIIIPPP’, the slope tearing. It was going off in both directions. That usually means game over.

As I looked up I could see the

Instantly an internal sense of dread and emptiness engulfed all the available space in my mind. This was it. Looking upslope I could see that we were about to experience the full fury of an immense slab snow avalanche. I also knew that few people live through this kind of experience and that by the time we saw it, there was no escaping it. I remember hearing Al yell, “Spread out! Spread out! She’s going!”

As the slope broke away, the initial noise of the avalanche was like two giant canvas tarps rubbing across one another. The snow slabs at the top of the avalanche began breaking up and churning, rising in a wave, like crashing surf. That surf line immediately engulfed Al, Marty, and Lynn.

Brad and I began running diagonally across and downslope vainly trying to escape the approaching wave front. It was rapidly gaining on me and I quickly realized I was not outrunning this avalanche. As I was trying to run I threw my pack off so I wouldn’t have my arms pinned back by the strap if I got buried. I also got rid of my ice ax. I didn’t want it flailing around near me if I got caught up in the churning mass that was chasing me.

It didn’t take long before I was hit by a six-foot high wave of wind-packed snow slabs. The initial impact threw me onto my back with my feet pointed downslope. I remember a sense of futility as I tried to “swim” to stay on top of the surface but the slabs kept riding up over my back and forcing me forward onto my stomach while driving me down under the surface.

It would be nice to report that during this time I was thinking of my four friends (who were all suffering as I was) and ways I could help them. However, the truth is that I was entirely focused inward on my own little microcosm of frigid chaos. All I focused on was my own survival.

I can clearly remember several little details about my rapid ride down the mountain. For instance, I found that when you are in an avalanche your hearing is very limited. You hear only what is right next to your ears. There are no sharp noises. Just a dull roar which gradually decreases as snow is driven into your ears, then just chaotic silence all around until all sense of up, down, right, or left is erased. I simply existed in this agitated blue-white frozen seascape.

I was being violently churned and battered around so much so that I recall waiting for one of my arms or legs to break. I had seen bodies after a slab snow avalanche and they were almost always twisted and broken, pulverized by the force of tons of snow cascading down a slope. I remember thinking this is going to hurt, this is going to hurt really bad. I realized it was more likely than not that I was going to die.

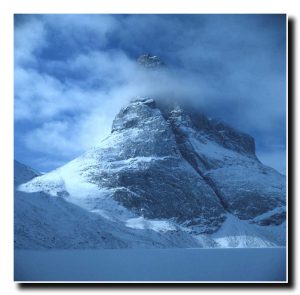

From Chapter 2, Ellesmere Island 1980

…Baffin Island was literally the most beautiful place I have ever been. As we skied down Walker Arm we nicknamed it “Wall Street” because it had granite spires on both sides of the fiord rising up four or five thousand feet right out of the water. It felt like you were in Manhattan but with buildings four or five times higher with these gorgeous aqua blue ice glaciers hanging off them.

…[but on Ellesmere] large crevasses were in many cases a hundred feet across, three to five hundred feet long, and several hundred feet deep. A wind-blown snow dome about one to two feet thick covered each one, rendering them nearly invisible to anyone amongst them on the surface of the glacier. They were a very dangerous and potentially fatal obstacle which we would now have to cross very carefully. As Al remembers, the sleds at that point again added to our woes.

“There is a lot of negative reality associated with falling into a crevasse with a 175-pound sled tied to your waist, and a 50-pound pack on your back,” he said, understating the truth. “There are a lot of components there that, even to the untrained eye, would seem problematic.”

…A very eerie and disconcerting nuance to this already riveting experience was the sound of icicles breaking off the bottom side of the thin snow bridges which hid the crevasses under us. We could hear them falling a hundred feet or more into these hidden monsters right under our feet. Sometimes the snow would simply fall away and a black hole would open under your skis. You could peer into the darkness and only hope that the snow bridge would hold until you had crossed.

“I suddenly heard things calving off below me,” said Errington. “I kept hearing this high crunching rattling sound. Steve was behind me and said he heard it, too. The idea of holding a fall if your partner broke through goes away because if that happened we were both going into the abyss in a spot where no one would have ever found us.”

…The team would, of course, try its best to extricate the victim and risk their lives to do it. But eventually, an awful decision might have to be made. Who would cut the rope?

…That evening after we had set up camp it was Marty’s turn to make dinner and he prepared beef stroganoff. It became obvious how wound up we were when Bill made an innocent comment about how the food could use a little pepper. Marty, usually the calmest, most polite person in our team took umbrage with the perceived insult to his cooking and quickly offered to give Bill more than just some pepper.

“Marty nearly bit his head off,” Al said while laughing. “He was so burned out from the ordeal and just couldn’t take any more. Steve and I intervened, walked him off and calmed him down. Basically, I explained that the rules of the Arctic didn’t allow him to kill a guy for asking for pepper.”

From Chapter 5, King William Island 1977

…As we hiked up the glacier we came across several five or six-foot wide streams of ice water coming down glacier fast on water-polished blue ice, then suddenly disappearing into a big black hole. If you ever slipped and fell into one of those streams you’d be gone. Just gone. There would be no stopping, no rescue and no body to recover. Fortunately, these dangerous mills make a lot of noise as the stream disappears down through the ice and give ample warning to beware.

…I was immediately drawn in and captivated by the tale of the Franklin Expedition, imagining what it would have been like to be marooned in the Arctic for three years, trying desperately to escape overland after abandoning their ships.

Over the years only a few mournful relics and bones had been found. This was a mystery that was to hold my attention for the next 25 years. In the beginning, I bought books on the subject and studied maps. Then like any interested sleuth, I began formulating my interpretation of the data based on my experience in the mountains and mountain rescue.

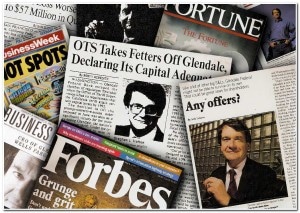

From Chapter 8, Banking at the Edge 1969 – 1998

Make no mistake, this was high stakes poker.

Early in the legal process, our lead attorney, with experience in these matters told me, “You have to be absolutely sure you want to do this because these are the nastiest, dirtiest playing adversaries you will ever meet. They will accuse you of everything and make your life miserable. They don’t just say ‘we’ll see you in court.’ They will do whatever they can to mess with you every step of the way. They are, after all, the Federal Government.”

At one point in the legal proceedings, I found out how true that was, when the government’s attorneys submitted court filings asserting that I was simply lying about all the money we claimed we were losing because of the breach. They were trying to have the case dismissed on the grounds that I was attempting to defraud the federal government.

If they could prove their theory I was told I would be subject to the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (the RICO act). If the government thought you had violated some portion of the RICO statues they had the authority to seize everything you had. Your entire net worth was on the line. They

“I can’t drop the lawsuit,” was my response. “I have a fiduciary responsibility to my shareholders and what’s left of the company. This lawsuit is a significant asset of the company and I cannot legally drop it nor would I, because it’s not the right thing to do. The courts have held that the government has breached the contract. You owe us damages.”

From Chapter 9, The Need for Speed 2007 – 2010

“I was still a little worried about Steve as a driver until the first time he ran on the salt after he got his AA license,” says Norwood. “I told him to go out and make a lazy pass. A nice, soft run. Steve goes out and goes 250 on the first run. He got back to the pits and asked me, ‘How’s that for a lazy pass?’”

“At Bonneville, the pits are midway down the track,” says Taylor. “You hear the car coming first, then you can see a small dot on the horizon and then the noise builds and all of a sudden it zooms past you, goes off into a mirage in the distance, and disappears. But you can still hear it going. We had to wait until each 5-mile qualifying run was complete before we could go get him. It takes a while because he’s driven several miles at 200 mph plus. During the licensing process, by the time we’d get to him, he’d have his driving suit off and his attitude was always very cool. He didn’t get excited or wonder why he wasn’t going faster. He immediately wanted to discuss what came next. He did a great job.”

I wasn’t necessarily the best driver Bonneville had seen, but I think I had some natural ability to drive because I soon developed a pretty good sense for what the car was doing. No matter how fast I was

Attaining the goal of being a successful driver at Bonneville requires the ability to maintain an intense focus on the job at hand.

Fortunately, my experiences in the mountains and Arctic, as well as in my career, had helped to develop that ability.

One incident I had while driving helped to confirm this. At one point during the 200 to 249 mph qualifying run, I was going around 240 mph and the driver’s side door popped open a crack. A door opening, even slightly, ruins the aerodynamics of the car, so it could have been a serious situation. I heard this noise, then the loud rush of air, and realized it was, in fact, the door. Not good. So I reached over, closed the door and kept accelerating down the track.

Problem solved.